24

March 2003

![]()

1. "The Jerusalem of Kurdistan", Kurds, Turks and Iraqis all vie for control of this city and its vast oil reserves Real battle will begin when war is over.

2. "Changing fortunes of the Kurds", the Kurds have been variously the vassals, allies, enemies, subjects and mercenaries of the Turks for more than 700 years.

3. "US will ignore Turkey's grey wolves at its peril", whatever the tactical differences between Turkey's armed forces and its politicians, there is no dispute over their ultimate strategic objectives. Perhaps the time has come to redeem the unfulfilled dream of Turkey's founder, Kemal Ataturk, who salvaged the republic from the ashes of the Ottoman empire in 1923.

4. "Old roots to Ankara's Iraq policy", Turkey says a flood of Kurdish refugees from northern Iraq would justify a military incursion.

5. "Turkish troops enter northern Iraq", Ankara ignores US warning of secondary battle front.

6. "Ankara and Washington agree on Turkish troops in northern Iraq", Ankara and Washington have reached agreement on the deployment of Turkish troops in a limited area skirting the border in northern Iraq, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said in a nationwide television address late Sunday.

1. - The Toronto Star - "The Jerusalem of Kurdistan":

Kurds, Turks and Iraqis all vie for control of this city and its vast oil reserves Real battle will begin when war is over

CIZRE / 23 March 2003 / by Sonia Verma

It was a late night telephone call from an old friend that finally

convinced the man he had to leave.

As war loomed, Iraqi intelligence was cracking down on the city of Kirkuk. The man's friend, a retired military officer, said his last chance would be lost if he didn't leave soon.

The man got out of bed and checked on his baby girl, still asleep in her crib. Then he woke his wife to break the news.

"Leaving was the only choice for me, but it was the hardest decision because my daughter and my wife could not come with me," he explains.

He left quietly the next morning, packing a small bag with a change of clothes, some photos of his family and his expired Turkish passport.

He travelled by car across a smuggling route into a Kurdish-controlled region of Northern Iraq, following the same route as thousands of other refugees who had left before him.

When the car approached Iraqi military checkpoints, he buried himself beneath sacks of grain in the trunk. It took a single day to reach the Turkish border crossing of Habur gate and a fragile freedom.

The man has few possessions from the city he left behind but carries with him the stories of a place that has become one of the most contested battlegrounds as the U.S. military attack on Iraq intensifies.

Kirkuk is a place where for years the secret police conducted a campaign of ethnic cleansing, tapping phones and searching homes, looking for signs of subversion. It is a city over which struggle will continue long after the war is over.

Two days after he left his home, the man sits in a deserted hotel lobby on the safe side of the Turkish border. He's still wearing the outfit his wife selected for his journey - rumpled khaki pants and a wool sweater to keep him warm.

He has not yet slept and his hands tremble when he speaks, reluctantly at first.

The man's name cannot be used for this story. He still fears for the safety of the wife and child he left behind.

"If the secret police found out I left, they would be killed," he says in an even voice.

The man was born in Turkey to a Kurdish family, but moved to the oil-rich city of Kirkuk three years ago when he married. His wife is a Turkoman, one of the ethnic Turks who make up less than 2 per cent of Iraq's population and whose status after the war remains uncertain.

People who live in Kirkuk call it the "Jerusalem of Kurdistan," because of the different ethnic groups who lay claim to it. Kurds have written a constitution declaring the city their capital, while Turkey's claim to the city dates back to the Ottoman Empire.

He had been living in Kirkuk illegally since his wedding, under the radar of a brutal "Arabization" plan designed to purge the population of people like him.

For more than 80 years, the Sunni Muslim-dominated governments of Iraq have tried to force Kurds and Turkomans to leave Kirkuk and replace them with Arabs.

When Saddam Hussein came to power, he introduced new measures which bar Kurds living in Kirkuk from owning property and registering businesses or marriages unless they adopt Arabic names.

Kurds were forced to undergo an "ethnicity correction" procedure, where they change their ethnicity from "Kurd" to "Arab" on all their official documents.

"I was afraid to ask them to renew my papers because I would have automatically become a target of the secret police," the man explains.

Already, his wife was under suspicion. Her brother was killed by government agents in 1980 because they believed he was working as an informant to the Turkish government, he says. The man feared he would fall to similar fate if he wasn't careful.

"They would have thought I was a government agent. I felt it was safer to live an anonymous life," he says.

But in the days leading up to the war, Saddam Hussein's regime started to bear down.

The Baath party conducted searches of houses up and down the street where he lived. They arrested people who were not members of the party and pressed others into military service for the Iraqi army.

"I knew it was only a matter of time until I was discovered," the man says.

When he left the city, Iraqi soldiers were gearing up for war.

They had buried explosives around the city's oil wells, mined the roads and built trenches in Kurdish neighbourhoods to guard against any rebellion.

He says soldiers dug a ring around the city and filled it with oil to set on fire in case of an attack. Anti-aircraft weapons were mounted on hill stations surrounding the city and trained on the sky. City roads were barricaded and the oil well behind the hospital was set ablaze a few days ago, he says.

"Everybody who lived there was trying to get out, but they were too scared to go to the Iraqi checkpoints. They kill them so nobody leaves," he says.

For those who remained in the city, life had come to a standstill before the bombs dropped. A 9 p.m. curfew was imposed, shops were shut down, school was cancelled and the buses stopped running.

"Everybody was waiting for the first bomb to drop. Of course they were afraid because they didn't know what was going to happen. They said, if the bombs start dropping we won't hide in our houses, we will stand in the streets. Maybe if they see us, they won't kill us," he said.

He believes Saddam Hussein's regime will fall and that the people of Kirkuk will welcome American troops as liberators.

"They're afraid right now to say they want to be freed. Even the army will welcome them," he predicts.

But he says the real battle for Kirkuk won't happen until after the war is over.

U.S. officials have said they want Kirkuk to be a multi-ethnic city, with oil revenue funnelled through a central government rather than to a single ethnic group.

But both Turkey and the Kurdish leaders of northern Iraq have stakes in Kirkuk, which is believed to hold 10 billion barrels of oil.

Turkey has already deployed more than 15,000 soldiers into Northern Iraq saying they have to secure the country's borders, and the Kurds are worried that Turkish troops will use the war as an excuse to occupy the region and take control of Kirkuk.

For their part, Kurdish military forces have assembled an underground resistance in Kirkuk and believe Kurds will eventually take control of the city by a massive influx of returning refugees once the war is over.

The man sitting in the hotel lobby will join them, returning to an uncertain future. Until then he will stay with his family in Istanbul and pray for the safety of his wife and child. He has not spoken to them since the bombing started.

"The minute I hear the war is over, I will find a

way of getting back to Kirkuk so I can kiss my wife and hold my daughter,"

he says. ![]()

2. - The Financial Times - "Changing fortunes of the Kurds":

ARBIL / 23 March 2003 / by Harvey Morris

The Kurds have been variously the vassals, allies, enemies, subjects

and mercenaries of the Turks for more than 700 years.

Now, Kurdish power is emerging on Turkey's doorstep in northern Iraq and Ankara fears the new mood of confidence there will spill over the border to influence its own Kurdish minority.

In the space of a few weeks, the Kurds of Iraq have replaced the Turks as the key US ally on the northern front of its war against Saddam Hussein. Turkish-US relations are at a low ebb and, for once in their history, Kurds have a great power on their side.

The Kurds were cheated of a state in the post-World War I settlement that brought about the establishment of the modern Turkish state. The new state incorporated the Kurdish populated territories of eastern Anatolia. The Ottoman province of Mosul - now northern Iraq - was seized by the British four days after the armistice and brought into the new Arab-dominated state of Iraq. The Kurds, fated to live astride the frontiers of great empires, were once again divided.

While the Arab subjects of the Ottoman empire were eventually to join the peoples of the Balkans in gaining their independence, the Kurds were to remain as the often unwilling subjects of newly emerging modern states.

The 1920 Treaty of Sevres, that opened the way for Kurds to choose the path of statehood was never ratified. Abandoned by the great powers that redrew the map of the Middle East, the Kurds lapsed back into obscurity, reduced to the status, in the official Turkish designation to that of "Mountain Turks".

In the early Middle Ages, at the time of the Kurdish-born sultan, Saladin, Kurdish princes rivalled Turks and Persians for power in the region, although they thought of themselves firstly as Muslims and only secondly as Kurds.

Inhabiting the ill-defined frontier between the Ottoman and Persian empires, they served both masters as some were later to serve in the armies of the Russian Tsars. The battle of Chaldiran in 1514, in which Kurds fought on both sides, fixed the frontier between the empires and in succeeding centuries the Kurdish princes were reduced to the status of vassals of the Sultan and the Shah.

Under the Ottomans, religion was more important than ethnic origin as a mark of status and the Muslim Kurds managed to retain much of their autonomy.

The Turkish geographer, Evliya Celebi, described in the mid-17th century the sophistication of the mountainous Kurdish provinces and the almost total independence of their lords.

"In these vast territories," he wrote, "live 500,000 men carrying guns. And there are 776 fortresses, all inhabited. Pray God that these districts of Kurdistan will remain for eternity as a barrier between the greatest of all dynasties, the House of Osman and the Shahs of Persia."

During the 19th century there were a dozen or more revolts against Ottoman power, often in response to the empire's attempts to limit Kurdish autonomy and enforce taxes. In the decades before the outbreak of World War I, a more modern strain of Kurdish nationalism emerged, echoing similar movements among the Ottoman empire's Balkan subjects.

After the war, some Kurds supported the struggle for independence, while others clung to the promises of Turkey's new rulers, who had promised that the new state would be a bi-national home for both Kurds and Turks. As the dream of statehood faded, so did that of a bi-national state.

The nationalists, led by Ataturk, who had won the support

of the Kurds by fostering their fears that the Christian Armenians planned

to annexe their lands, instituted a policy of Turkification. Kurdish

irregulars were used in the massacre of Armenians carried out during

the war, although some Kurdish leaders expressed the fear that the Kurds

might be the next target. In 1924, Ataturk suspended the National Assembly,

which had many Kurdish members. The Kurdish language was banned. It

is not so surprising, given the ambivalent nature of the long Turkish-Kurdish

relationship, that the chief ideologue of the Turkification policy was

a Kurd. ![]()

3. - The Asia Times - "US will ignore Turkey's grey wolves at its peril":

25 March 2003 / by K Gajendra Singh*

Whatever the tactical differences between Turkey's armed forces

and its politicians, there is no dispute over their ultimate strategic

objectives. Perhaps the time has come to redeem the unfulfilled dream

of Turkey's founder, Kemal Ataturk, who salvaged the republic from the

ashes of the Ottoman empire in 1923.

In 1919, when Ataturk and his comrades had begun organizing a war of resistance for Turkey's independence, then under the heels of World War I victors led by Great Britain, their map of a sacred new nation included, apart from the present-day boundaries of Turkey, the Kurdish province of Mosul (with Kirkuk), now in Iraq. Much of this area had been occupied by the British forces after the ceasefire in 1918 and was later joined with the former Ottoman Arab vilayets (provinces) of Baghdad and Basra to create Iraq. But this divided the Kurdish homelands. From Iraq too, the sub-province of Kuwait under the Kayakayam of Basra was detached to create a new emirate. Oil was then, as it is now, the main driving force; not the freedom or welfare of the people. The British colonial policy of encouraging and then creating dissension and divisions can be seen elsewhere, too, in the world - the Indian sub-continent, Palestine, Cyprus and Ireland.

In a fast-evolving strategic situation in the region, there might be an opportunity to take back oil-rich Mosul and Kirkuk, many Turks feel. Almost all political leaders, including those from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), media writers and others have reiterated the country's claims on Kirkuk. One of the reasons for going into north Iraq is to protect their kinsmen the Turkomans and their rights over the reserves of oil around Kirkuk. This area is now under the control of Saddam Hussein's Sunni Arabs, but it has been traditionally claimed by the Kurds, who are in the majority in the region. The other major reason cited, of course, is Turkish fears of Kurds declaring an independent state after the collapse of the Saddam regime.

Turkey has paid dearly during the past two decades because of almost autonomous Kurdish enclaves in north Iraq, which have inspired and assisted a fierce rebellion for independence among its own Kurds, who form 25 percent of its population. During the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s and after the 1991 Gulf War, the rebellion reached its heights. Since the beginning of the Marxist PKK (Kurdish Workers Party)-inspired rebellion in 1984, over 35,000 Turkish citizens have been killed, including 5,000 soldiers. The struggle has also shattered the social and economic fabric in the south and east of Turkey. The problem is now under control after a 1999 ceasefire was declared and the capture of PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan. His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment last year and the ban on the use of the Kurdish language for education etc was eased.

Therefore, ignoring protests from foes and friends alike, the Turkish armed forces have regularly moved in and out of north Iraq to punish Turkey's residual Kurdish rebels who shelter there. It has regularly maintained some presence in Kurdish north Iraq, which was stepped up even before Turkey's parliament on March 21 authorized its troops to enter Iraq, along with granting permission to the US to use its air space to transport troops and hardware for a possible second front in Kurdish north Iraq. Turkish troops are now reported to be in north Iraq, estimated to be between 2,000 to 5,000 strong. Ever since the US administration took a decision to attack Iraq to bring about a regime change in Baghdad, even without UN sanction, serious differences and strains have emerged, not only with the US's NATO allies in Europe, but also with Turkey.

In order to conduct a successful and short war to minimize world opprobrium, as well as casualties and costs, the US asked for permission for the use of Turkish bases in southeast Turkey to station 62,000 US troops in order to open a second front against Iraq. The request was made in the US's usual insensitive fashion of public "bribing" and arm-twisting. It was irritating to hear daily broadcasts or claims that in spite of a package of nearly US$30 billion in grants and loans, Turkey was not taking the bait. Turkey has lost tens of billions of dollars following the sanctions imposed on Iraq since 1990. It is one of the major reasons for the current economic malaise in Turkey.

The new and inexperienced government of the AKP, especially its leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, was agreeable to provide bases to the US, but a massive majority of Turks (now 94 percent) have remained opposed to a war on Muslim Iraq. Iraq has been the friendliest of Turkey's mostly inimical neighbors until very recently. Many AKP deputies belong to southeast Turkey with Kurdish and Arab blood relations across the borders with Iraq and Syria.

Turkish president Ahmet Sezer, a former head of the Constitutional Court, has always insisted on international legitimacy before waging a war on Iraq. Before the March 1 vote that rejected the US request, he had impressed his view on the speaker of parliament. It was a somewhat confused situation. With tens of thousands of Turkish citizens protesting passionately in front of parliament and elsewhere, it further pressurized the newly- elected and divided deputies. The AKP government had come into almost absolute power unexpectedly after last November's elections, but its leader Erdogan had still to be elected in a by-election to become prime minister. This led to more confusion, with diffused decision-making centers. A day before the parliamentary vote, Turkey's military-dominated, highest policymaking body, the National Security Council, had dared not take a decision to recommend a vote for the motion in the face of overwhelming public opposition. After five hours of discussion, it left the decision to the government and parliament.

While Erdogan was enthusiastic, many in the party were opposed to giving approval. The government-supported motion, with the ruling party boasting two-thirds of the deputies in a 550-member parliament, was lost on March 1 when nearly 100 ruling party members voted against it, along with the opposition. The vote was lost by only 4 votes. This stunned the US, stumping its war plans. It certainly slowed down the preparations for the northern front. But the US still hoped that once Erdogan was elected to parliament and became prime minister, a second vote would be held.

In an unusual move, the Turkish armed forces' Chief of General Staff, General Hilmi Ozkok, issued a statement on March 5 extending its support to the government in "its option to open a second front against Iraq in the event of war [which] would shorten the conflict and minimize casualties". He said, "Turkey's support of the US would also reduce the harm to its economy." At the same time, Ozkok clarified that it was the right of parliament to reject the proposal to station US forces in Turkey, but "the Turkish armed forces' view is the same as the government's". He explained that the military had not made public its views earlier to avoid the impression of trying to influence the vote. "If we had expressed our views, it would have amounted to pressurizing the parliament for the approval of the resolution," he said. "It wouldn't have been democratic."

Ozkok pointed out that the Iraqi problem was a vital and multilateral issue having political, social and legal dimensions. Agreeing that 94 percent of the people said "no" to war, he added. "We, as soldiers, know the violence and dimensions of war and oppose the war most. It is obvious that we will suffer major damage whatever Turkey's move if a war starts. Turkey can face political, economic, social damage and also damage to its security." Ozkok went on to say, "It is a reality in the current stage that Turkey does not have the possibility and capability to prevent a war on its own. I wish the war could be prevented. Unfortunately, our choice is between the bad and worse, not between the good and bad." He noted that Turkey would suffer losses in any case, but if it joined the US, it would be compensated. He believed that it would also eliminate unexpected political developments in the north of Iraq.

Being a member of NATO since the early 1950s, Turkey's armed forces have a very close relationship with the US military brass. Turkey is heavily reliant on the International Monetary Fund, controlled by the US, to bail it out of its current acute economic problems and ease the weight of massive external debt payments. This was a failsafe position for Turkey. If the US carried out a short and quick war successfully, Turkey would play a major role in the reshaping of Iraq. If in the unlikely event of a peaceful solution of the problem, Turkey would have won enough brownie points with the US.

But after taking over as prime minister, Erdogan had a better appreciation of all the pros and cons, including in his party. It might even split. Sensing the mood of the country and in his party, he continued to stall the second vote while the US continued with its arm-twisting tactics, which further annoyed the Turkish leadership, media and the public. The US then said that it would change its war plans and fly its troops and arms from Romanian and Bulgarian bases and elsewhere to north Iraq. It said that it would do without Turkish bases and withdrew its financial package.

On the whole it was an unappetizing show, as it has been between the US and the UK on the one side and France and Germany on the other. Some US ships were diverted to the Red Sea, but many still wait at Turkish ports to unload military hardware for transfer to the war front in southeast Turkey.

Statements and counter statements, bullying tactics, threats and defiance between the US and Turkey have left no less deep a chasm than between the Atlantic alliance's Western members. There is a lot of confusion, acrimony and misunderstanding aired publicly, even after an agreement was passed in parliament for the US to use its air space. Reportedly, the Turkish government had even refused the US its permission for 24 hours unless Washington agreed to let Ankara send its troops to northern Iraq.

Secretary of State Colin Powell had three phone conversations in 48 hours with Erdogan to bring him round. The confusion continued when US officials said that the US had not agreed to Turkish demands, but senior Turkish officials said that they had reached an agreement with Powell that allowed them to add to the troops they already had in north Iraq. The confusion, which even included reports of Turkish troop movements into north Iraq, came amid high tension between the two NATO allies and clenched teeth comments by US officials (Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld did show commendable restraint, though). Later on, it turned out that fresh Turkish troops had not entered north Iraq after all. But the ill will, rancor and suspicions remain.

For the moment it appears that the US will not be utilizing much of the airspace facility as its plans have already been completely upset in north Iraq. Incidentally, a few days before the terms were agreed to, a US Special Forces team in north Iraq ran into trouble with Iraqi forces and requested air support. Turkey rejected the request. While the US forces escaped unharmed, Turkey's refusal stunned Pentagon and State Department officials. Verily, US-Turkish relations have hit a nadir after years of close cooperation.

Compare this to the 1950s, when the Soviet Union, one of the victors of World War II, had staked claims over two northeastern provinces of Turkey and some control over the Bosphorus Straits. A nervous Turkey, which had rightly kept out of the war, as it did not want to be first devastated by the Nazis and then liberated by the Soviets, went begging to the US for protection. It sent a brigade to the Korean War to fight until the last man. Since then, through thick and thin, the allies have stayed together. Now, only a bitter taste in the mouth.

There is a lesson for all. A bully who can browbeat or thrash smaller kids, sooner or later arouses hostility and resistance in the whole community. Something like that coalesced between the last week of February and the first week of March. Turkey's democratic institutions, the region's largest democratic republic, rejected a US troop presence on Turkish soil as American ships waited off the Turkish coast.

After five days, it appears that the war is not turning out to be the cake walk that it was made out to be to the US public. Iraqis are not welcoming and hugging the US as "liberators". US soldiers have been taken prisoner, and there have been battle fatalities, apart from casualties of "friendly fire".

What will happen in north Iraq? Without wider agreement and more support from Turkey, with the second largest armed forces in NATO, the war which the US and the UK have embarked on could end up disastrously in north Iraq. Even if all goes well, the US will still need Turkey as a strategic partner in the now inflamed region. But the US will have to pay a price. Otherwise, the "grey wolf" will await and seize its opportunity.

Note.The ancestors of the Turks are said to have been brought up among wolves. Hence, the young, the brave and the bold call themselves grey wolves - also a term favored by extreme nationalists.

* K Gajendra Singh, Indian ambassador (retired), served

as ambassador to Turkey from August 1992 to April 1996. Prior to that,

he served terms as ambassador to Jordan, Romania and Senegal. He is

currently chairman of the Foundation for Indo-Turkic Studies. ![]()

4. - The Christian Science Monitor - "Old roots to Ankara's Iraq policy":

Turkey says a flood of Kurdish refugees from northern Iraq would justify a military incursion

ANKARA/ 24 March 2003 / by Ilene R. Prusher

To understand Turkey's vote supporting its right to send troops

to northern Iraq, look no further than Kirkuk and Mosul, two oil-rich

cities that tell the story of Turkey's own manifest destiny. It's a

tale that continues to develop today, driving Turkish policy on Iraq

and further straining relations between Ankara and Washington.

Since the controversial parliamentary vote late last week, the US has been trying to dissuade Turkey from entering Iraq unilaterally. Yesterday, Ankara announced that Kurdish refugees in northern Iraq had not advanced toward the Turkish border, which Turkey says would justify a military deployment.

Iraqi-held Kirkuk and Mosul - which Kurdish, Turkish, and American forces could home in on in coming days - have long sat like Turkey's unrealized hinterlands. According to Turkish history books, European powers, engaged in a duplicitous "Great Game" at the end of World War I to carve up the Middle East, deprived the crumbling Ottoman Empire of Kirkuk and Mosul - regions founding father Kemal Ataturk saw as belonging, without question, to the nascent Republic of Turkey. As compensation for their loss, Turkey was promised some 10 percent of the oil revenues of Iraq. The money came "in fits and starts," says Ankara University professor Dogu Ergil, and after 13 years, it stopped coming all together. A line item for the Iraqi oil revenue still appears in Turkey's national budget each year - next to it, a blank space.

"It is in the public conscience, no matter what anyone says, that those areas are meant to be within Turkey's borders," says Ahmet K. Han, a political economist at Istanbul Bilgi University. "Turkish students learn that Mosul and Kirkuk were intended to be part of the natural borders of Turkey, in the misak-i milli," he adds, using the Ottoman Turkish term for Ataturk's vision of Turkey's boundaries as agreed upon in the country's founding National Pact.

To be sure, few Turks today talk about the misak-i milli. But most here hold as sacred the tenet that Turkey can and must prevent Iraqi Kurds - many of whom were forced out of Mosul and Kirkuk by Saddam Hussein - from gaining control of the cities. With their own oil, Turkish officials argue, Kurds could make a Kurdish state economically viable. In Turkish minds, that would spell the end of Turkey's borders because it would prompt Kurds in southeastern Turkey - around 20 percent of the country's population - to fight to join a new Kurdistan.

The very concept of a far-away superpower enforcing new ideas of "regime change" digs up old resentments at having been swindled out of lucrative territory Turkey saw as its natural soil.

But for those with a shorter view of history, the last US-led war against Iraq triggered many of Turkey's current economic and political problems. The 1991 Gulf War ended normal trade relations between Iraq and Turkey. The war also closed down an oil pipeline from Kirkuk to Ceyhan, Turkey, causing Turkey to lose revenue it collected from transporting the oil to the Mediterranean Sea. Turkey also blames the first Gulf War's flood of refugees for allowing thousands of guerrillas in the Kurdistan Worker's Party (PKK) to slip into Turkey, heating up a violent separatist war.

The pipeline was repaired in 1996. After years of sanctions, Iraq was allowed to sell some of its oil under the United Nations-administered oil-for-food program. But tight controls on Iraqi oil, Turkish officials complain, have kept the pipeline carrying a third of what it could. The pipeline's capacity is 81 million tons of oil per year, according to figures from Turkey's main energy agency, but last year it carried only 31 million tons. Unofficially, however, far more Iraqi oil has been entering Turkey.

Along with Syria, Jordan, and others, Turkey was a regular customer for inexpensive smuggled oil, diplomatic sources here say. The US for several years ignored the black market trade in part because Turkey was also buying diesel oil from autonomous Kurds in northern Iraq, which was pivotal to Kurdish development under the cover of the no-fly zone. "The diesel trade was about turning a blind eye so that Kurdish groups, the KDP and PUK [Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan] could pay salaries," says a European diplomat here who asked not to be named. In May of 2000, Turkey began to regulate the diesel trade more tightly, in part because the government realized it was losing a chance to collect revenue, and in part because it worried that the Kurds - particularly the KDP - were becoming too affluent, and perhaps inching too close to independence. "Turkey woke up to the fact that they were losing tons of money," the diplomat says.

The US also feared that the smuggled oil was being used by Hussein to secretly rebuild his arsenal. Valerie Marcel, an expert on Iraqi oil and Middle East politics, says that Hussein at the very least could use the proceeds to strengthen his hand within Iraq. "It's quite likely that a lot of the money he earned was used to consolidate his power," says Dr. Marcel, of the Royal Institute for International Affairs in London. "It doesn't only go to rearming, but proceeds that come from smuggling are the ones that you spend on the most politically sensitive things, that you don't want to the UN to see."

US officials had hoped that the promise of an oil pipeline pumping at full pulse, normalized trade, and a stable, democratic Iraq on Turkey's borders would convince Turkey to join Washington's drive for regime change.

But through Turkish lenses, changing the status quo raises more problems than it solves. The dynamics of the unofficial oil trade made it even more uncomfortable for Turkey to make a decision about allowing the US to use its bases for a northern front. "Both over-the-counter trade and the smuggled oil were drivers for Turkey in maintaining good relations with Iraq. And the Iraqi government hoped such deals would tie Turkey to the Iraqi regime and make it a stakeholder in Baghdad's authority," Marcel says.

Although Turks are no fans of Hussein, Iraqi oil sold

by a centralized regime in Baghdad is preferable to oil controlled by

an Iraqi Kurdistan. The Bush administration last week reiterated its

stance: There will be no independent Kurdistan, and Iraq's territorial

integrity will be preserved. But, looking back over more than a few

disappointments, Turks remain deeply skeptical - enough to risk a strain

in relations with the U.S. and move towards sending more troops into

northern Iraq, a gambit no one but Turkey finds agreeable. ![]()

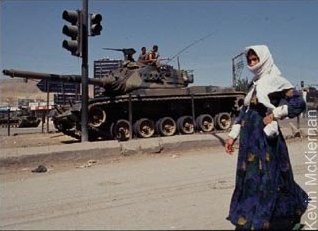

5. - The Guardian - "Turkish troops enter northern Iraq":

Ankara ignores US warning of secondary battle front

WASHINGTON / ZAKHO / 22 March 2003 / by Oliver Burkeman

and Michael Howard

Turkey began sending troops across the border into Iraqi Kurdistan

last night, a move which threatens to open a "war within the war"

and hugely complicate the American military strategy in Iraq.

The Turkish foreign minister, Abdullah Gul, announced the incursion after an apparent breakthrough for the coalition's northern front yesterday, when Ankara finally gave overflight rights to US planes.

During the days of hard bargaining Turkey demanded the right to send troops into Iraq as a condition for allowing the overflights. But enraged US officials said last night that Washington had not agreed and had told Turkey to "stay the hell out".

About 1,000 Turkish soldiers crossed the border, augmenting the several thousand it has there to pursue Turkish Kurd guerrillas. Another 5,000 were moving through Turkey to mass on the border.

Donald Rumsfeld, the US defence secretary, said: "We have special forces units connected to Kurdish forces in the north ... and you can be certain that we have advised the Turkish government and the Turkish armed forces that it would be notably unhelpful if they went into the north in large numbers."

The secretary of state, Colin Powell, visibly irritated, had said earlier: "We don't see any need for any Turkish incursions into northern Iraq."

"We told them to stay the hell out, and it is a major problem which we are going to be watching very closely today," an unnamed senior official told CNN.

Turkey said it would send troops to avert a humanitarian crisis in northern Iraq, to hold back a flood of refugees into Turkey, and to prevent terrorists crossing its border.

Mr Gul said. "A vacuum was formed in northern Iraq and that vacuum became practically a camp for terrorist activity. This time we do not want such a vacuum."

The US is deeply apprehensive of a secondary war if Kurdish fighters clash with the Turks, potentially bringing chaos to the coalition's attempt to advance on Baghdad from the north and threatening the Kirkuk oil fields.

Turkey fears instability and attempts by Iraqi Kurds to establish an independent state, perhaps by seizing control of the oil fields. The 4m Iraqi Kurds, for their part, fear that a Turkish force could take away their freedoms and condemn them to the same fate as Turkey's 13m Kurds.

The Turks entering north Iraq may begin hunting the remaining members of Kadek, the militant group formerly known as the PKK.

Last week, Osman Ocalan, brother of the group's imprisoned leader Abdullah Ocalan, promised a violent retaliation if Turkish troops crossed the border.

The US won its overflying rights after weeks of reversals, and they are only a fraction of the help it sought, which included stationing 62,000 service personnel there.

Iraqi Kurds living near the border were leaving their homes yesterday. Lieutenant Massoud Rushdi, a recent graduate from the Zakho military academy, said his wife and two sons were leaving because they knew that Turkish tanks could soon cross the bridge over the Zakho river and crush their 12-year experiment in self-rule.

"We decided that it was not safe for them to stay," he said. "If Turkey wants to help us fight Saddam, they are welcome. But if they come here to prevent us being free, we have the right to defend ourselves."

The Kurds of Zakho are preparing to resist. "We don't want to be liberated from Saddam only to be oppressed by Turkey," said Ahmed Barmani, a car mechanic. "I hate Turkey more than I do Saddam."

He joined his childhood friend Massoud to dig themselves into a defensive position overlooking the river.

"Wherever they try to cross, we'll be ready for them," he said.

The two friends were not alone. Several hundred peshmerga fighters from the villages around Zakho could be seen taking up positions in the hills.

There is little that they, lightly armed, can do to stop the Turks, who have the second biggest army in Nato.

But Babekir Zebari, a regional commander of the Kurdish military forces, said life would be made very difficult for Turkey if it tried to occupy the self-rule area.

"If they disturb our situation, we will disturb theirs," he said.

"Saddam has been unable to defeat us; neither will

the Turkish generals." ![]()

6. - AFP - "Ankara and Washington agree on Turkish troops in northern Iraq":

ANKARA / 23 March 2003

Ankara and Washington have reached agreement on the deployment of

Turkish troops in a limited area skirting the border in northern Iraq,

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said in a nationwide television

address late Sunday.

Erdogan announced that Ankara and Washington had made "military arrangements (for) a limited belt along the border aimed at stopping a possible influx of refugees... and prevent certain threats to our security.

"The presence of Turkish soldiers in that region will be a source of security and stability for Turkey and the region," he said.

Protecting the territorial integrity of Iraq was essential and "Turkey and the United States have reached agreement on all questions," Erdogan added.

Ankara fears the Kurds in northern Iraq may declare independence and fuel unrest with its own Kurdish minority, while Washington has been worried a Turkish deployment would spark clashes with the Kurds it has enlisted to fight Baghdad's forces.

Erdogan's statement brought a sharp response from Iraq.

Turkey will "pay dearly" if it sends troops into Kurdish-held northern Iraq, Iraqi Foreign Minister Naji Sabri warned.

"Turkey is acting against its people and it will pay dearly if it is drawn into the colonising campaign being waged on Iraq," Sabri told reporters in Cairo ahead of a meeting of the Arab League on Monday.

Washington has also warned Turkey against intervening in northern Iraq, wanting to avoid possible clashes between Turkish forces and Kurdish groups in territory where United States special forces are preparing for an assault on the oil towns of Kirkuk and Mosul.

"We're making it very clear to the Turks that we expect them not to come in to northern Iraq," US President George W. Bush told reporters on Sunday.

"We're in constant touch with the Turkish military as well as Turkish politicians. They know our policy.

"And they know we're working with the Kurds to make sure there's not an incident that would cause there to be an excuse to go in," he said.

Iraqi Kurds, who have not been under the control of Baghdad since the end of the 1991 Gulf war, have vowed to fight Turkish troops if they invade the territory they hold.

Ankara fears the Iraqi Kurds might declare independence if Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein is ousted, possibly reigniting an insurgency among its own sizeable Kurdish community in the southeast, which is only just recovering from a 15-year bloody rebellion for self-rule.

Ankara also perceives threats to its security from local Kurds and Turkish Kurdish rebels in hiding.

Erdogan said in an interview in Newsweek magazine that Washington had agreed to Turkish troops entering a 19-kilometer (12-mile) zone in northern Iraq.

Although NATO-member Turkey has been one of Washington's strongest allies, the refusal by the Turkish parliament to allow the United States to use the country to deploy 62,000 troops and open a northern front in Iraq threw a spanner in US war plans.

The three-week delay in approving overflight rights for

US warplanes also irritated Washington, which on Saturday finally abandoned

plans to open a northern front in Iraq via Turkey and ordered the troops

waiting on transport ships in the Mediterranean to the Gulf. ![]()