3

October 2002

![]()

2. "Party jockeying obscures stakes in Turkish elections", on October 1, Turkish Parliament resumed after summer recess and closed, defying legislators who want to postpone November 3 elections by keeping Parliament in session. While elections appear set to go ahead, similar political maneuvers will dominate the campaign season.

3. "Turkey pulls a fast one", Tayyip Erdogan was tipped by the polls to replace Bulent Ecevit as prime minister until Turkey's supreme judiciary banned him and three other opposition candidates from all political posts because of their records of sedition, a move which runs contrary to recent EU-linked reforms.

4. "Cypriot leaders in last-ditch attempt at unification", pressure mounts as deadline nears for joining EU.

5. "EU delivers Turkish membership snub", the EU has serious doubts about Turkish membership.

6. "Once-feuding Iraqi Kurds to meet amid unity talk"

1. - The New York Times - "Turkey, Mindful of Kurds, Fears Spillover if U.S. Invades Iraq":

TUNCELI / 3 October 2002 / By CRAIG S. SMITH

The traditionally rebellious Kurds of this hardscrabble hill town

live hundreds of miles from the Iraq border, but tensions that bristle

so obviously here could erupt into fresh violence against the Turkish

government if the United States invades Iraq.

At least, that's what the Turkish government contends.

The virtual autonomy enjoyed by Iraqi Kurds — thanks to American and British enforcement of a no-flight zone over northern Iraq — is likely to increase if the government of Saddam Hussein is ousted

Indeed, Iraqi Kurds are asking for a Kurdish administrative district within an Iraqi federation.

That, Turkish officials say, would reawaken Kurdish nationalism here, feeding dreams of the same kind of independence for Turkey's estimated 12 million to 20 million Kurds.

"It's already having an effect on the political atmosphere in southeastern Turkey, and that effect will increase," said Umit Ozdag, chairman of the conservative Turkish policy institute Asam. "Kurds are going to ask for the same political framework in Turkey" that the Iraqi Kurds would enjoy in a post-Hussein Iraq.

[Turkey's prime minister, Bulent Ecevit, underscored the government's concerns about Kurdish nationalism in an interview published Tuesday in Hurriyet, a Turkish daily. "Many steps have already been taken toward the establishment of a separate state," he said. "Turkey cannot accept this to be taken further."]

Turkey is pressing the Bush administration to restrict the rights and territory granted Iraqi Kurds in any future Iraqi government, arguing, for example, that the country's northern oil fields should be kept out of Kurdish hands. But many Turkish Kurds insist that northern Iraq has nothing to do with the tension here and that Turkey simply wants to avoid giving them full cultural and political rights.

In August, Turkey's Parliament did approve constitutional changes abolishing the death penalty and legalizing private Kurdish-language education and Kurdish-language broadcasts. The hotly debated changes are required to qualify for membership in the European Union, which Turkey would like to join.

But the reforms have yet to be carried out, and Kurds complain that their rights are still being denied.

Turkey fought a 15-year civil war against the Kurdistan Workers' Party, which once hoped to establish an independent Kurdistan. Serious fighting stopped three years ago when the party declared a cease-fire and withdrew its battered forces to the Kurdish regions of Iraq.

While some Turkish Kurds warn of a new uprising if Turkish oppression continues, many say they are fed up with war and have abandoned the dreams of independence. Encouraged by a birthrate that suggests they could eventually overtake Turks as the country's main ethnic group, Kurds have turned to politics to pursue full rights.

"Kurds in Turkey don't favor separation, nor are they standing with a request for federation in their hand," said Murat Bozlak, former chairman of the recently disbanded Kurdish political party, Hadep, at the party's headquarters in Ankara. "Their only wish is to be given democratic and cultural rights equal to those of every citizen."

But those rights have been slow in coming, in part, some Turks say, because politicians and the ever-powerful military are reluctant to countenance democracy overall. "Of course there's a danger Kurds may want a federal state in Turkey as well, but that's their democratic right," said Dogu Ergil, a political science professor at Ankara University. "The fear isn't of what Kurds will say, but of democracy itself."

Generations of Turkish leaders have sought to force the Kurds' assimilation into the larger Turkish population. For decades, speaking Kurdish was outlawed and Kurds were officially designated "mountain Turks."

Kurds say the repression is the main reason for more than two dozen revolts in the last 80 years. An estimated 30,000 people died in the fighting that erupted in the 1980's after the Kurdistan Workers' Party took up arms and Turkey responded with emergency rule that turned the southeast into a network of army checkpoints.

Even today, with emergency rule — a limited form of martial law — lifted in all but two Kurdish cities, travelers are stopped and checked by soldiers about every 10 miles, and many towns remain off limits to outsiders without government approval. In Tunceli (pronounced toon-JEH-lee), armored personnel carriers still stand sentry on the approach roads and heavily armed soldiers continue to keep watch from hilltop bunkers.

At the last checkpoint before Tunceli — which residents still call Dersim, its Kurdish name — foreigners are required to sign a form stating that they will not stray from the main road.

The town itself is an isolated outpost reminiscent of Wild West towns, and the mood is tense. A former farmer whose village was burned down eight years ago said the town had been brutalized by the military. In 1996, he said, soldiers dragged the body of a 25-year-old man through the streets as a warning to others after the man was caught giving bread to two Kurdish fighters, who were also killed.

"The government is a criminal gang," said a middle-aged man late one night at a table crowded with bottles and cigarette butts in a Tunceli restaurant. "All we want is democracy and to live peacefully with everyone else."

At the local Hadep office, a party official, Ali Can Unlu, explained that the Kurds felt robbed of rightful control of their town. When the vote was being counted for mayor three years ago, he and other witnesses say, the police cleared the room with three ballot boxes yet to be opened and the Hadep candidate leading by 100 votes. The Hadep candidate lost. "If they start to deny language and cultural rights again, people will return to a revolutionary state," Mr. Unlu said.

To some extent, the denial of cultural rights is routine. Berdan Acun, for example, a fresh-faced lawyer in nearby Ergani, went to record his son's birth at the local registrar nine months ago. But the office refused to accept the name he had chosen for his child, Hejar Pola, which in Kurdish means "valuable steel." The office director, a woman he had known for years, would not give a reason.

The authorities regularly reject Kurdish names. Most people do not want trouble, so they choose another. But after being repeatedly rebuffed, Mr. Acun is preparing to take his case to court. "He has no name yet," said Mr. Acun as his son played on the family's living room carpet, "but he will."

The subgovernor of nearby Silopi, Unal Cakici, grew visibly angry when asked about the rules on Kurdish names. "If someone applies to me with a name that I don't understand, I will refuse it, too," he said. "Terrorists are trying to use all sorts of methods to create problems and this is one of them." Mr. Cakici said the outside world had failed to appreciate the depth or viciousness of the threat posed by Kurdish separatists.

Although the Kurdish military threat has largely abated, the European Union finally put the Kurdistan Workers' Party on its list of terrorist organizations this year. In the past, the group assassinated officials and killed entire Kurdish families for collaborating with the government.

Political gains by Iraq's Kurds could revive Turkish separatism and renew that threat, Turkish officials say. Turkish Kurds dismiss the government's fears, saying they are dedicated to finding a political solution. Yet in time that could well include a federal Kurdish state in southeastern Turkey, a prospect that sends shudders through governing circles in Ankara.

Kurdish-language programming produced in Belgium and beamed into Turkey on Medya TV, a Paris-based satellite station, refers frequently to Kurdistan, and occasionally shows maps giving the outlines of the idealized Kurdish state covering parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran.

The staff in a small office at Hadep headquarters in Ankara, listening raptly to the programming, said Turkish Kurds recognized that an independent Kurdistan was an impractical dream.

"Personally," said a young hazel-eyed man, "I

think it would be better to have a federal system." ![]()

2. - Eurasianet - "Party jockeying obscures stakes in Turkish elections":

1 October 2002 / by Mevlut Katik

On October 1, Turkish Parliament resumed after summer recess and

closed, defying legislators who want to postpone November 3 elections

by keeping Parliament in session. While elections appear set to go ahead,

similar political maneuvers will dominate the campaign season.

Parties in Ankara are channeling their energies into preventing nationally known politicians from running, in light of a law that requires a party to win 10 percent of a vote to gain seats in Parliament. The parties are targeting each other rather than appealing to voters because they are vying in a fragmented field – and because procedural challenges to opponents have lately proved effective. The supreme election board ruled on September 20 that the leader of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), Recep Tayyip Erdogan, could not run because a court had convicted him of inciting religious and ethnic hatred in 1998. (He had publicly recited a popular poem with militaristic and religious imagery.) Erdogan’s party still leads the polls, and the laws at issue have been reformed since Erdogan’s conviction and no longer apply. However, the election board declined to decide where legal changes became binding, judging instead that anyone ever convicted of a crime cannot run for office. The ban also fell on former prime minister Necmettin Erbakan, a strident Islamist, and on activists representing human-rights and Kurdish causes.

As President Ahmed Necdet Sezer warns that he can dissolve the eventual government if it fails to coalesce, Erdogan’s banishment has diluted the elections’ force. He has continued to tour the country as the head of his party, telling reporters on October 1 that he hopes Turkey will “soon become a model democracy.” If the AKP wins the elections, deputy party leader Abdullah Gul will probably replace him. However, the election board gave Erdogan a chance to re-enter the government, saying that if his criminal record is quashed he would be eligible to stand for future parliamentary membership. His future candidacy would presumably not damage AKP’s popularity. Since constitutional changes in 2002 strengthened Turkey’s commitment to free speech, the principal effect of the board’s September 20 decision may be to prevent the most popular candidate from winning office.

Other candidates with strong bases may also lose the chance to serve the new government. Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit’s Democratic Left Party (DSP), and the Motherland Party (ANAP) led by Deputy Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz, may not garner 10 percent of the vote. These parties, which currently form a governing coalition, have dominated Turkish political life since the 1980s. But opinion polls indicate that they may not be able to make their case in the next government. The Nationalist Action Party (MHP), another coalition partner, also faces elimination; so may the True Path Party (DYP), the principal opposition faction. MHP leader Devlet Bahceli has dismissed opinion polls that suggest both parties border on 10 percent of the vote. He derided parties that wanted to delay elections at a September 28 rally. “Their goal is very obvious: to establish a government without the MHP,” the news agency Anatolia quoted him as saying. Meanwhile, the DYP formed an alliance with the Democratic Turkey Party (DTP), reportedly boosting its chances of entering parliament.

Whoever ends up in the legislature, all this jockeying seems unlikely to break Turkey’s cycle of crises. It also will probably discourage public debate on the benefits and obligations of joining the European Union, which will consider Turkey’s application in December. On several occasions since Ecevit relented in July to pave the way for elections, the government has seemed on the brink of collapse. Yilmaz said his party would break the coalition if the MHP continues to block reforms aimed at easing Turkey’s accession. [For background, see the Eurasia Insight archives.] Yilmaz also called on September 13 and on September 30 for postponing elections until after the European Union’s December gathering. Yilmaz presumably has calculated that his party would bask in the glow of a European welcome. However, his visible maneuvering may be to blame for his party’s sagging popularity and for defections by leading party members. By courting crisis, Yilmaz may end up in a party locked out of the next government.

Parties that do not make it into the new parliament may perpetuate a focus on politics rather than on policy. Some have already put out feelers about changing election law to fuse party lists or lower the cutoff to 5 percent. Former Foreign Minister Ismail Cem’s young party, the New Turkey Party (YTP), already favors lowering the threshold. This is a less ambitious platform than the popular Cem promised when he announced his new party in July. Cem spoke then of promoting religious freedom, tolerance of ethnic Kurds, and market-oriented reforms. With Ecevit holding onto power, such goals seem stifled. And all these political games suggest that old habits in Turkish political life may be harder to break than Cem or other reformists might hope.

These old games are, however, occurring in a new context. Civil society institutions have more legitimacy to oppose political manipulation than they used to. Moreover, the position of the presidency, strengthened over the years in reforms, now acts as a bulwark against chaos. President Sezer has reminded squabbling politicians that he can dissolve Parliament if it fails to govern. A trained lawyer and jurist, President Sezer may manage to end the postponement turmoil. Even if he does, though, one might conclude that the party system still needs reform. The shenanigans of the past several weeks, coming after reforms and on the eve of possible admittance to the European Union, should show Turkish politicians that governing this democracy will require more adroit thinking after November 3.

Editor’s Note: Mevlut Katik is London-based journalist

and analyst. He is a former BBC correspondent and also worked for The

Economist group. ![]()

3. - The Middle East Times - "Turkey pulls a fast one":

2 October 2002 / by Lucy Ashton Special to the Middle

East Times

Tayyip Erdogan was tipped by the polls to replace Bulent Ecevit

as prime minister until Turkey's supreme judiciary banned him and three

other opposition candidates from all political posts because of their

records of sedition, a move which runs contrary to recent EU-linked

reforms.

A fortnight previously, new laws inspired by Turkey's wishes to join the EU allowed Erdogan to successfully appeal against his sedition charge and have his record wiped clean.

Turkey is suffering its worst economic recession in 60 years. Were it not for an IMF emergence loan of $3 billion and the promise of a further $12 billion the country would be bankrupt – a loan linked to economic, rather than political, reforms.

Entrance to the EU and revival of the economy are central issues in Turkish's November election, but it may be the government's fear of political liberals as much as conservatives that are delaying the possibility of EU accession.

To most Turks the EU and its democratic ideals sound appealing – they mean money, investment, more global influence and increased human rights.

But while the governing and business classes tout democratic intentions, the recent banning order on Erdogan and two other liberals suggests a truly free vote in Turkey may have brought a socialist Islamic-based government to power – something obviously neither the liberal middle-class Turk, the judiciary or the army want or will allow.

As the popular mayor of Istanbul in 1994, Erdogan's relentless cleaning up of the city won him much praise, even among his critics. After the severe earthquake in 1999 his party provided emergency aid 50 hours before the government did.

The origins for Erdogan's focus for a welfare state have proven controversial, and have been denounced by critics as overtly Islamist – accusations which Erdogan denies.

Erdogan is not one for masking his religious convictions, however. In 1998, after he read a poem with religious undertones, he was sentenced to ten months in prison for Islamist sedition.

Turkey is a secular democracy in an Islamic nation, with the army – thanks to Kamal Ataturk - the guarantors of state stability. Ataturk insured that should the government move outside of secularism, it can be legally replaced by the military in what would effectively be an automatic coup.

Since 1960 Turkey's government has ritually been ousted in this way every decade, most recently in 1997 when then then-prime minister Necmettin Erbakan of the Welfare Party, a previous Islamic-based party, was found guilty of Islamic sedition. The Welfare Party was dissolved and he was banned from politics for five years.

Before the final Erdogan verdict, Ecevit warned that the army might intervene again should Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (the AK) win the election.

Though sedition specifically means inspiring revolt, the official court declaration issued in a speedy ten days was dramatically extended to Erbakan as well as Murat Bozlak, leader of the Hadep (the Kurdish party) and Akin Birdal, the head of Turkey's Human Rights Association.

The moves were slammed by the nation's press.

"The nation has been robbed from the right to vote for Erdogan, Erbakan, Bozlak or Birdal. Is this how a democracy should function?" commented the Turkish Daily News on September 21.

"The ban is on the nation. This situation has to

change dramatically if we are to have any chance of even arguing that

we are entitled for a place in the EU." ![]()

4. - The Guardian - "Cypriot leaders in last-ditch attempt at unification ":

Pressure mounts as deadline nears for joining EU

NICOSIA / 3 October 2002 / by Helena Smith

The ethnic Greek and Turkish leaders of Cyprus will hold crucial

talks today in an effort to reunite the island ahead of the country's

anticipated accession to the European Union.

After 28 years of failing to bridge their differences, Cypriot President Glafcos Clerides and Rauf Denktash, the leader of the republic's breakaway Turkish north, have only two months for an amicable solution to the west's longest-running diplomatic dispute. On December 14, the island, which meets all the EU's stringent economic criteria, is expected to be invited to join the union as part of its enlargement.

Failure to reach a settlement before then is likely to put Greece and Turkey, both Nato members, on a collision course if Ankara acts on its frequently made threat to annex the breakaway northern rump state.

Leaving Cyprus for New York, where today's talks have been convened by Kofi Annan, the UN secretary general, Mr Clerides described the coming months as "the most important diplomatic battle of the past 28 years - a battle that will determine the future of this country".

The internationally recognised Greek Cypriot government is nominally negotiating EU entry on behalf of the whole island. However, Mr Denktash has snubbed the invitation to participate in the negotiations with Brussels, and Turkey has repeatedly warned that it will seize the outlawed northern territory if the island is allowed to join the before a settlement is reached.

This week Ankara announced the creation of a joint parliamentary committee to examine ways of further "integrating" the north.

"On the issue of Cyprus, we have to resist until the end," the Turkish prime minister, Bulent Ecevit, said on Tuesday.

Annexation, say analysts, would damage Ankara's relations with Brussels and wreck any chance of EU membership for Nato's only member in the Muslim world.

"If that were to happen, Muslims around the world will see it as evidence that the west will never grant an Islamic country a place at the table of economic prosperity," said John Sitilides of the Western Policy Centre, a Washington thinktank.

In a televised address to the nation before leaving for New York, Mr Clerides said the internationally recognised south was "silently" strengthening its defences "to meet any eventuality".

Ankara has recently augmented its military presence in the north. Some 35,000 Turkish soldiers have been stationed there since invading the island in response to a Greek-led coup in 1974.

Concern about Cyprus has been reinforced by the lack of any evident progress since the two leaders re-engaged in face-to-face, UN-sponsored peace talks 10 months ago.

The negotiations have stumbled on the unwavering demand for international recognition by Mr Denktash, who derives support from Turkey's military top brass.

The Cypriot foreign minister, Ioannis Cassoulides, dispelled the fear that a settlement was virtually impossible before the EU's Copenhagen summit this December. Much depended on whether European-oriented reformists won Turkey's general election on November 3, he said.

"Nobody can exclude that a settlement can take place," he told the Guardian. "In view of her own [EU] expectations, Turkey may well change position. When the Turks change, they often do so abruptly. We will continue the talks right up until the very last day."

Cyprus would gain EU admission - with or without a solution - "because no one wants to make a mess of enlargement", Mr Cassoulides added.

Mirroring Ankara's threats, Athens has repeatedly warned that it "will have no other option" but to veto the accession of the nine other mostly ex-communist countries competing for EU entry, if Cyprus's application is turned down. "Whoever dares to stop Cyprus, stops EU enlargement," said George Papandreou, the Greek foreign minister, when he met Mr Annan last month.

Member states such as the Netherlands have voiced strong reservations about admitting the island before a political settlement that would allow Greek and Turkish Cypriots to join the EU at the same time, arguing that they do not want the EU's borders to end at a barbed-wire fence.

Diplomats say that while time is now of the essence, much of the problem has in fact been resolved, thanks to two decades of relentless UN-brokered peace talks and behind-the-scenes negotiations.

"We always knew that with Cyprus things would go

to the wire," one well-placed EU envoy said in Nicosia. "But

it's also fair to say that 90% of the problem has been solved - it's

just a question of putting the ticks in the boxes." ![]()

5. - BBC - "EU delivers Turkish membership snub":

The EU has serious doubts about Turkish membership

BRUSSELS / 2 October 2002 / by Oana Lungescu

The European Union will not endorse Turkey's demands to set a date

by the end of the year for beginning entry talks.

During a discussion about the EU's expansion plans on Wednesday, some members of the European Commission apparently raised doubts that Turkey could ever become a member of the EU.

As it prepares for general elections next month, Turkey has already warned the EU that it would provoke a crisis if, by the end of the year, it had failed to set a date for starting membership talks.

It is a risk the EU seems prepared to take.

According to senior EU sources, the European Commission believes it is impossible to give, even indirectly, a date for Turkey.

Several commissioners apparently raised serious doubts that Turkey could ever become a member of the EU.

Some commissioners have reportedly compared Turkey to Morocco or Ukraine in terms of suitability for membership.

Next week's report is expected to be highly critical about alleged torture in Turkish prisons.

Muslim factor

Concern over human rights is the main reason why Turkey has been waiting for years to start membership talks, but the debate indicates a general unease in the EU over admitting a big Muslim country in its midst.

There will be better news for the other 12 applicant countries, mostly from former communist bloc. Ten of them will be told they could conclude entry talks by December and join in 2004.

But they face a period of strict monitoring.

The European Commission will introduce strict mechanisms to measure how they apply EU rules. And if they are found wanting, they will be warned entry into the EU may be delayed or even cancelled.

Senior EU sources say Poland has the biggest problems in adopting the EU's massive rule-book.

In agriculture, officials say, the problems are enormous, and seven applicants out of the 10 face difficulties implementing EU competition laws.

Lagging even further behind are Romania and Bulgaria.

They hope to join in 2007, but the European Commission

will give them no fixed date next week. ![]()

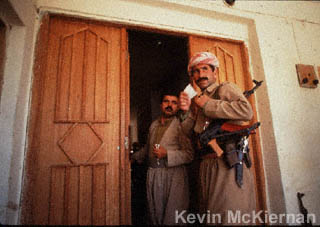

6. - Reuters - "Once-feuding Iraqi Kurds to meet amid unity talk":

Barzani's Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) said he would visit rival leader Jalal Talabani in Talabani's home province of Sulaymaniyah for the first time since "the fall of Kurdish consensus and the start of internal conflict in 1994-1998".

"This meeting is significant as it will open a new page of Kurdish harmony and unity. The two leaders will discuss political developments and... will agree to strengthen Iraqi Kurdish unity in the face of increasing challenges," KDP said in a statement.

ISTANBUL / 3 October 2002

Iraqi Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani said he would on Wednesday

visit the home base of a rival for the first time since 1994, as the

prospect of U.S.-led attacks on Iraq adds impetus to their reconciliation.

The Kurds of northern Iraq broke away from Baghdad's control in the wake of the 1991 Gulf War and seem sure to form a part of any U.S.-led bid to oust Iraqi President Saddam Hussein.

The United States has protected the mountainous Kurdish enclave from government attack with air patrols for more than a decade and invested years of diplomacy into uniting the two feuding Kurdish factions that run the region.

Barzani's Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) said he would visit rival leader Jalal Talabani in Talabani's home province of Sulaymaniyah for the first time since "the fall of Kurdish consensus and the start of internal conflict in 1994-1998".

A U.S.-brokered ceasefire in 1998 put an end to years of sporadic fighting between the pair over territory, power-sharing and revenues from border trade.

"This meeting is significant as it will open a new page of Kurdish harmony and unity," Barzani's party said in a statement.

"The two leaders will discuss political developments and ... will agree to strengthen Iraqi Kurdish unity in the face of increasing challenges," it said.

The meeting comes two days before a milestone meeting of a Kurdistan parliament designed to formalise the new warmth between the rival groups that were fighting as recently as 1998.

The division of seats in the assembly has long been a bone of contention between the KDP and Talabani's Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and it has not met since 1996.

Eyes on future

The two parties late last month agreed on a draft constitution for the kind of Iraq they would like to see if the United States ousts Saddam.

The charter sees the oil-rich city of Kirkuk -- currently run by the Iraqi government -- as capital of the Kurdish region.

That, as well as the trappings of statehood such as a Kurdish flag, alarms Turkey, which is opposed to the formation of any separate Kurdish state out of any turmoil in Iraq.

Barzani and Talabani have both tried to allay Turkey's fears, insisting they see themselves as part of a united, federal Iraqi state.

The Iraqi government deeply resents Turkish and U.S. military activity inside northern Iraq and on Wednesday urged the breakaway Kurdish groups to return to the fold.

"We are waiting for them to come to their senses and to cooperate with the Iraqi government and to reach an agreement with the Iraqi government," Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Tareq Aziz said during a visit to the Turkish capital Ankara.

Turkey keeps troops inside northern Iraq to strike at its own Kurdish rebels who use the region as a base, something Aziz said would be impossible if Baghdad was in charge there.

"When Iraq was in full control of that region Turkey

did not suffer from any security threats. Turkey has been suffering

from those security threats because the Iraqi administration is not

in place there," he said. ![]()