11

June 2002

![]()

1. "Turkish economist risks trial for calling Ocalan "mister"", a Turkish prosecutor has launched a preliminary probe against a well-known economist for referring to Kurdish rebel leader Abdullah Ocalan as "Mr. Ocalan," Anatolia news agency reported on Monday.

2. "The banning of organisations and why News Labour backs the Turks over the Kurds", the practice of legally banning terrorist organisations has always seemed as pointless as it is inconsistent.

3. "Despite PM's assurances, Turkey's stock market drops", Turkish Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit's insistence that his fragile coalition is working well despite his faltering health and disputes over EU-sought reforms failed Monday to defuse worries over stability as the volatile stock market fell further.

4. "Kurdistan Dispatch: Bomb Shelter", by Michael Rubin.

Dear reader,

owing

to technical maintenance measures there is only a reduced "flash

bulletin" on Tuesday, June 11. Our up-to-date service will be resumed

as usual on Wednesday, June 12.

The staff

1. - AFP - "Turkish economist risks trial for calling Ocalan "mister"":

ISTANBUL / 10 June 2002

A Turkish prosecutor has launched a preliminary probe against a

well-known economist for referring to Kurdish rebel leader Abdullah

Ocalan as "Mr. Ocalan," Anatolia news agency reported on Monday.

TV commentator and newspaper columnist Atilla Yesilada caused an uproar

during a conference in Istanbul on Saturday when he referred to Ocalan

as "Sayin," the Turkish word for "mister," which

also means honorable and esteemed.

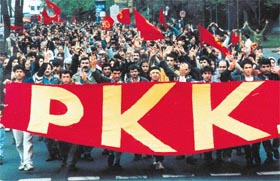

Far-right minister for foreign trade Tunca Toskay walked out of the conference in protest after Yesilada, wearing a baseball cap and a t-Shirt reading "Public Enemy," insisted on using the word and urged those unhappy with it to leave the hall. "We will not stay at a platform where a man with the blood of 30,000 people on his hands is called 'mister,'" Toskay said while storming out, according to media reports in the weekend. Ocalan is the leader of the separatist Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which has fought a 15-year for Kurdish-self rule in southeast Turkey, with the conflict claiming some 36,500 lives.

Prosecutors have launched a preliminary investigation into Saturday's incident in Istanbul's district of Sile, at the end of which they will decide whether Yesilada should be formally indicted, Anatolia said. Turkish authorities usually react harshly to any acts or remarks that could mean support or sympathy for Kurdish separatism. In an e-mail letter to the organizers of the conference, obtained by AFP on Monday, Yesilada sought to defend himself.

"I have never felt any respect neither for the PKK

nor its coward head Ocalan and... I have always defended Turkey's just

struggle againt the PKK. But I am a defender of human rights to the

very end," Yesilada wrote. ![]()

2. - New Statesman - "The banning of organisations and why News Labour backs the Turks over the Kurds":

New Statesman / 10 June 2002 / MarK Thomas

The practice of legally banning terrorist organisations has always

seemed as pointless as it is inconsistent. If Blunkett were to ban organisations

that represent the interests of ideological dogma driven minorities

who take peoples lives, large sections of Britains railways would have

been banned years ago. Railtrack would issue a statement renaming itself

The Real Railtrack (continuity wing). Maintenance contractors would

have to hold their Annual General Meetings in secret and company directors

would be hurried into the room in banaclavas and shades before announcing

that years dividend. I know some of you are already muttering "Mark

Mark you can't compare railway companies to the IRA or the UVF."

You are right of course, the IRA would normally phone in a warning before

they killed a member of the public.

Surely it must have occurred to Blunkett and previous home secretaries that potential terrorists are not going to be put off joining terrorist groups by the fact that the groups are banned. As a rule people who are prepared to plant bombs and commit murder generally have a disregard for legal niceties. Expecting banning orders to reduce terrorism is a little bit like expecting the Highway Code to prevent drive by shootings. When was the last time anyone saw groups of armed men speeding from a killing shouting "Mirror signal manoeuvre! For God?s sake do you want to lose points on your license."

Jack Straw 's banning of 21 foreign organisations early last year lead the way for much of Europe?s over reactive anti terror laws, which followed in the wake of the attacks upon the World Trade Centre. However, it was perhaps the inclusion of the PKK (The Kurdish Workers Party) on the list of 21 that caused most concern. The PKK have fought a cruel war with the Turkish state, over 30,000 people were killed, between 3- 4 million Kurds were displaced and about 3,500 Kurdish villages and towns have been destroyed. The PKK are not angels and they have undoubtedly committed atrocities but three years ago they declared a cease-fire, which has by and large held. They also announced their intentions to seek a Kurdish state through non-violent democratic means. Had the PKK been Irish republicans or Northern Irish loyalists their behaviour would not have seen them banned. On the contrary, by now their leaders would be running education departments or stomping around in a sash pretending that thuggery in a bowler hat amounts to culture.

So why did New Labour ban the PKK in April 2001? The answer, as it is with many questions of New Labour, is money and business. Turkey is the Richard Desmond of the British arms and construction world. They might attract bad publicity but they do put their money in the right places. New Labour may well be embarrassed in taking pornography?s profits. They may even flinch at the thought that men up and down the country are helping finance the Blair project by purchasing materials to masturbate with. Although I imagine many porn fans feel just as tainted knowing their money could end up in Labour's coffers. However, when it comes to working and promoting trade with a state that has the worst human rights record this side of Iraq Labour have no qualms. Perhaps if the Turkish authorities published "Hardcore pictures of Torturers wives!" New Labour might be less keen.

Quite simply the PKK were banned to please a valued client. The rest of the European Union followed suit on the 2nd May 2002 adding the PKK to the list of terrorist organisations, despite the fact that the PKK disbanded itself in April.

Turkey is enjoying it's new found international muscle and is about to take command of the 18 nation UN security force in Afghanistan. Saudi Arabia's reluctance to allow US planes to operate from there has left the field open for Turkey to play host to Bush's bombers, which is especially important if Iraq is going to be invaded. None of this will be lost on the EU.

The day after the EU decision , May 3rd, Turkish police arrested 11 members of Egitim-Sen ( The Education Union) in Mardin. Their crime was learning the Kurdish language. According to Egitim-Sen the 11, including a pregnant woman

Sermin Erbas, were subjected to beatings, denied food for 3 days and nights, had plastic bags forced onto their heads, left naked and assaulted with pressurised hoses. Sermin Erbas fell into a coma as a result of this treatment, she is still in a critical condition.

That same day emboldened by the EU action the Turkish military began operations in the Kurdish areas with their customary arbitrary detention and torture. On the May 25th the Turkish military entered the Kurdish region of Metina in Iraq. According to local reports thousands of soldiers deploying tanks and rockets on the ground and cobra helicopters in the air began their attack at around 3.30am. It is claimed at least 17 people have lost their lives. The EU?s actions far from preventing terror appear to have hastened it, they have given Turkey the green light for its human rights abuses.

Now Turkey is calling for KADEK (the political party formed

by the PKK) and HADEP a longstanding pro Kurdish democratic political

party to be banned in Europe. To most Kurds this is the equivalent of

trying to outlaw Sein Fein and the SDLP. To ban the PKK as terrorists

is bad enough but in doing so the UK and the EU have actively encouraged

Turkey's own state terror. ![]()

3. - AFP - "Despite PM's assurances, Turkey's stock market drops":

ANKARA / 10 June 2002 / By Hande Culpan

Turkish Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit's insistence that his fragile

coalition is working well despite his faltering health and disputes

over EU-sought reforms failed Monday to defuse worries over stability

as the volatile stock market fell further. The national index of the

Istanbul stock exchange plunged 238 points, or 2.3 percent, to end morning

trading at 9,912.9 points -- under the psychological barrier of 10,000

points -- compared to last week's closing figure of 10,151 points.

The Turkish lira also fell to 1.475 million to the dollar from 1.459 million in the highest bid on the interbank money market. "The markets are focused on political uncertainty," Burak Utku, an economist from Garanti securities, told the NTV news channel. "The several forthcoming weeks are very critical. If at least some of the political uncertainty is not eradicated, we cannot expect a very healthy market," he added. The markets -- jittery since Ecevit, 77, has been hospitalized twice since early May -- also remained indifferent to the cabinet meeting here, the first in six weeks, in a bid to prove right assurances that the three-party coalition is doing its job.

The council of ministers, which had last met on April 29, convened under the chairmanship of far-right deputy Prime Minister Devlet Bahceli, and discussed secondary issues in the absence of Ecevit. Despite increasing calls for him to resign, Ecevit, a five-time prime minister, insisted Sunday that he would not resign and maintained that his health problems were not creating a power vacuum.

"There is no question of distancing myself from the affairs of state. I have no intention of leaving government duties," he told a press conference, where he made his first public appearance in more than 10 days. He also said that the coalition government was working "in harmony" despite differences over reforms demanded by the European Union so that it could begin talks to join the 15-member bloc.

Government stability is vital for Turkey at a time when it is implementing a three-year austerity programme with 16-billion-dollar loan from the International Monetary Fund, and is pressed to make good on its bid to join the Union. But analysts were unconvinced by his assurances. "Bulent Ecevit is not the prime minister," Cuneyt Ulsever wrote in his column in the mass-circulation Hurriyet daily. "He has lost all legitimacy in the eyes of the public."

In addition to losing the faith of the people, there is a more near threat to Ecevit's goverment: his own coalition partner, Bahceli, issued a veiled threat last week of quitting the government if the other two parties seek alliances with the opposition on key EU reforms. The MHP remains opposed to steps such as scrapping the death penalty -- it wans to see condemned Kurdish rebel leader Abdullah Ocalan hanged -- and legalizing education and broadcast in the Kurdish language on the grounds that it could fan ethnic separatism.

Ecevit, who has missed two crucial meetings aiming to

discuss steps needed to fulfill Ankara's EU aspirations, on Sunday appeared

unphased by the threat and played down fears that there would be "serious

divergences" over the reforms. But, the mood is quite different

among brokers. "There is an increasing possibility for the government

to collapse," Hakan Avci from Global Securities told AFP. ![]()

4. - New Rebublic - "Kurdistan Dispatch: Bomb Shelter":

June 17, 2002 edition / by: Michael Rubin

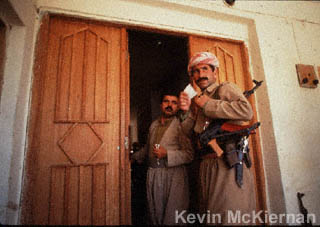

"At the very best, you might have met Jesse Jackson; more likely,

you'd be in an unmarked grave," chided the Kurdish minister. He

was not happy. It was the spring of 2001, and a friend and I had accidentally

crossed from the Kurdish opposition-controlled portion of Iraq into

government territory. The line of control had been easy to miss. The

last checkpoint on the Kurdish side looked like any other - two or three

soldiers armed with Kalashnikovs politely checking passenger IDs and

occasionally opening trunks to search for illegal weapons. The white

Toyota Land Cruiser we were driving looked like those used by the United

Nations, and the Kurds at the checkpoint simply waved us on. From there

we expected to enter the one-to five-kilometer noman's- land that normally

separates Kurdish and government territory.

We crossed a bridge over the Zab River, and 50 meters later came to another checkpoint. About a dozen soldiers lounged near a large howitzer emplacement. Then my friend pointed to the howitzer and asked with alarm, "Isn't that gun pointed the wrong way?" We slowly turned around, returning to the Kurdish safe haven before Saddam Hussein's soldiers were any the wiser.

Our memories were correct: The territory just beyond the Zab River had been no-man's-land. But roughly one year earlier, Iraqi troops had occupied it; and when the United States didn't respond, they dug in. "If the Americans would have reacted, they would have retreated," one Kurdish soldier explained.

For the Kurds, the remilitarization of no-man's-land is one more sign that when it comes to confronting Saddam, the United States can't be trusted. And that's a big problem, because without Kurdish help the Bush administration's on again, off-again invasion plans may be off for good. The two primary Iraqi-Kurdish leaders, Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani -- who head the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), respectively - administer a chunk of Iraq twice the size of New Jersey.They control 50,000 lightly armed peshmerga (literally, "those who face death") as well as a number of small airfields, many of which were cleared of debris in March ("to provide better picnic grounds," Kurdish officials told the populace). While the landing strips would need to be lengthened to accommodate jet fighters, basic infrastructure exists for helicopters and smaller planes and can be quickly upgraded for more sophisticated aircraft. (Indeed, the Turkish army occasionally uses the Bamerni Airfield near Sarsang.) In addition, scattered throughout the region are concrete fortresses built by Saddam and now used by refugees, the United Nations, or peshmerga -- fortresses that could be easily secured for use by American rear-guard troops as armor and ammunition depots. While the United States can oust Saddam without Kurdish assistance, a ready made staging area in northern Iraq would lessen our dependence on unreliable Persian Gulf partners like Saudi Arabia -- which would make any military campaign a whole lot easier.

But right now the Kurds aren't keen to put their resources at America's disposal. In April, Barzani and Talabani refused permission for the CIA to renew a permanent American presence in the region. Efforts by American diplomats to convince the two Kurdish leaders to jointly sign a public document outlining a joint vision for a federal Iraq have come to naught. In February both KDP and PUK refused to allow an Iraqi National Congress (INC) radio transmitter on their territory, even though both parties are members of the INC. That same month Barzani declared to The Wall Street Journal, "We will not be party to any project that will endanger what we have achieved." While most Iraqi Kurds despise Saddam as a mass murderer and would like nothing more than to see him deposed, they don't want to provoke him without guarantees that Washington is serious. And based on past U.S. behavior, they aren't convinced that if they rise up once again, Washington will finish the job.

The leaders of the Iraqi Kurds have long memories compounded by a sometimes self-defeating obsession with foreign betrayal. "How can we trust the United States?" Barzani asked me rhetorically in an interview last spring. "You only care about your own interests, not ours." He illustrated his contention with a narrative of U.S. abandonment centered around three key incidents. The first occurred in 1975 when Henry Kissinger brokered the Algiers agreement, suspending (temporarily, it turned out) the then-low-grade conflict between Iran and Iraq (full-scale war erupted five years later). As part of the deal, Kissinger effectively pulled the rug out from beneath the Iranian-supported Kurdish rebellion in Iraq, forcing tens of thousands of Iraqi Kurds into Iranian refugee camps. In a January 2000 interview, Deputy Kurdish Prime Minister Sami Abdul Rahman called Kissinger's actions "the most cruel betrayal in our history -- which is full of betrayals."

The second American betrayal came in 1987 and 1988, after up to 182,000 Kurds died in an ethnic-cleansing campaign that began when the Iraqi government bulldozed more than 4,000 of the 4,650 Kurdish villages in northern Iraq and culminated in Saddam's use of chemical weapons against civilian Kurds. While Saddam carried out the infamous Halabja attack allegedly in retaliation for Kurdish militia support for Iranian forces, most of the villages attacked and destroyed were civilian and far from the Iranian frontier. But in order not to antagonize Saddam, whom the United States was then seeking to engage, the United States denied knowledge of the ethnic cleansing. Three years later a map noting each destroyed village -- compiled using American satellite intelligence, printed by the Pentagon's Defense Mapping Agency, and declassified for use by U.S. troops at the start of the Gulf war -- proved America's duplicity.

Finally, the Kurds hold the United States largely responsible for the failure of their post-Gulf war uprising one decade ago. On February 15, 1991, President George H.W. Bush called on "the Iraqi military and the Iraqi people to take matters into their own hands, to force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside." And the Kurds, along with antigovernment Shia in Iraq's South, dutifully rose up -only to have the U.S. military withhold air cover and let them be crushed. Many Kurds believe that the United States was not simply feckless, but that it wanted the rebellions defeated. "If the U.S. wanted us to oust Saddam, we could have," Mam Rustam, a PUK commander, explained. "But instead the Americans released the Republican Guard POWs, just in time for them to rearm, remobilize, and attack us."

And over the past two years the United States still hasn't won the Kurds' trust. In September 2000 Secretary of State Madeleine Albright outlined the Iraqi provocations that would result in the use of American forces: "We do not want to see [the Iraqi government] reconstitute their weapons of mass destruction, and we don't want them to take action against the Kurds, and we don't want them to threaten the neighborhood." And indeed, in December 2000, when Iraqi troops crossed the thirty-sixth parallel and surrounded Ba'adre, a town on the line of control, the United States responded, and Saddam's men quickly retreated. I visited Ba'adre soon after the incursion ended. Residents described how U.S. warplanes flew low over Iraqi lines and 138 Iraqi troops threw down their weapons and surrendered without a shot.

But the Bush administration, despite its tough talk, hasn't kept up the pressure. In May 2001, Iraqi forces probed Kurdish defenses near the dusty town of Kifri without any American response. Just last month U.S. intelligence reported increasing Iraqi MiG fighter activity inside the nofly zones, a clear violation of the post-Gulf war arrangement. Around the same time, Iraq moved armored units and infantry to within artillery range of Irbil, the Kurdish regional capital. Kurds hoped the Bush administration would take the cue and respond to the provocations militarily. But the Bush administration has done no such thing.

In fact, the rare moments of American toughness only underscore the Kurds' chronic disappointment. On February16, 2001, U.S. jets pounded Iraqi radar installations outside Baghdad after Iraqi anti-aircraft batteries targeted no-fly-zone patrols. I was working out at the University of Dohuk's gymnasium when the news first came in. "Finally, the U.S. shows it is serious," a businessman remarked, a view repeated by others. But faced with State Department criticism, President George W. Bush never epeated the operation despite continued Iraqi noncompliance, in effect signaling to Saddam that the new administration was unwilling to consistently back up its bluster with action.

The Kurds have also lost faith because successive American administrations have hedged on commitments for the sake of legalism. In August 1996 (and on subsequent occasions as well) Washington refused to respond when Iraqi helicopters moved north of the thirty-sixth parallel -- since technically the no-fly zone applies only to fixed-wing aircraft. But that distinction makes little sense to the Kurds, who see little substantive difference in being strafed by Iraqi planes, shot by Iraqi helicopters, or machine-gunned by Iraqi armor. The Kurds are also frustrated by Washington's inconsistent interpretation of the boundaries of the Kurdish safe haven. Initially it was 36 square miles and centered on the town of Zakho -- though it later expanded to include Dohuk as well, bringing the total area to a much larger 3,600 square miles. In October 1991 Saddam withdrew his administration from huge swaths of territory in an attempt to starve the recalcitrant Kurds into submission; his food and fuel blockade failed, and the Kurds filled the vacuum, expanding their control to nearly 15,500 square miles. If Saddam orders his forces to attack that expanded territory, the Kurds worry that the United States might say it has no obligation to protect anything beyond Dohuk and Zakho, putting more than three million Iraqi Kurds outside those two cities at risk. Successive U.S. administrations have failed to clarify their position on how exactly they define the safe haven, leaving Iraqi Kurds confused about and unimpressed by Washington's socalled red lines.

If Bush is serious about finishing Saddam, he needs to do more than opine about the "axis of evil." He must give clear guarantees of military support and protection to the Iraqis on the ground who will bear the brunt of the fighting, whether as combatants or bystanders. Bush must also let Saddam know that use of chemical weapons against Iraqi civilians (i.e., the Kurds) will draw the same massive retaliation as the use of chemical weapons against American forces. Only then will he have a chance of convincing Kurdish leaders to assist U.S. regime- change plans in Iraq. As Talabani told me over breakfast in his Sulaymaniyah office last year, "The United States . . . has a role, and will have a role if -- and put two lines under that 'if' -if the United States is serious." So far the Bush administration hasn't even put one line.

Michael Rubin, an adjunct scholar at The Washington Institute

for Near East Policy, spent nine months in northern Iraq last year as

a Carnegie Council fellow. ![]()