31

July 2002

![]()

2. "Eyes On Turkey", the government is collapsing. The economy is a mess. Voters are fed up. The stage is set for an Islamic party to take power. Should Europe—and the world—worry?

3. "Death toll rises to 52 in Turkish prison hunger strike", a hunger strike by Turkish prisoners against controversial jail reforms claimed its 52th victim Tuesday, a human rights group said. Semra Basyigit, a 24-year-old woman detainee, died in an Istanbul hospital, one year after joining the hunger strike, a member of the Human Rights Association (IHD) told AFP.

4. "Selling out to set stage for an attack on Iraq", Reports that the Bush administration is prepared to write off the more than $4 billion that Turkey owes the United States could not be a clearer sign that the president's plans for a "regime change" in Iraq are moving into high gear. Turkey is the one country whose support is crucial in that endeavor because no effective military action against Saddam Hussein is conceivable without the use of U.S. military bases on Turkish soil.

5. "U.S. Should Bolster Ties to Turkey", Turkish leaders are fond of describing their country as a bridge. Turkey, with its commercial center in Istanbul, straddles the continents, bringing Europe and the Mideast together.

6. "Iraqi Kurds set to seal agreement on implementing four-year-old peace deal", the two main Kurdish factions sharing control of northern Iraq are poised to seal an agreement on the implementation of contentious provisions in a 1998 US-brokered peace deal, informed sources said here Tuesday.

Dear reader,

Due to the holiday time our "Flash Bulletin" will not be forwarded to email addresses from August 1, 2002 until August 25, 2002. It can be viewed, however, in the internet at www.flash-bulletin.de as usual.

1. - AFP - "Turkish parliament set to decide on plan for snap polls in November":

ANKARA / 31 July 2002 / by Hande Culpan

Turkish legislators were set to vote Wednesday on holding early

elections in November, a plan which has robust support from all parties

in parliament except belaguered Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit. A simple

majority of votes from the MPs present Wednesday in the 550-seat assembly

would be sufficent to adopt the proposal for bringing elections forward

to November 3 from April 2004, and advocates of snap polls are largely

tipped to be able to garner the necessary support.

An overwhelming majority of the 25 MPs on the parliament's constitutional commission approved the plan on Tuesday, thus paving the way for the decisive vote in the general assembly. Only three deputies from Ecevit's Democratic Left Party (DSP) voted against the proposal. Wednesday's vote comes in the wake of several unsuccessful attempts by Ecevit to drum up support to thwart snap polls, which he says would further set back the troubled economy and could threaten the secular system of the mainly Muslim country.

The 77-year-old prime minister had agreed to early elections earlier in the month after his shaky three-party coalition government lost its parliamentary majority, but has since adamantly rejected such a move. According to the horror scenarios Ecevit has raised, polls could derail a crucial economic recovery programme backed by a 16-billion-dollar loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) at a time when the economy is showing signs of coming out of its worst recession in years. Ecevit also claims that polls could propel into power Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a popular politician with an Islamic background, which could have stormy repercussions in a country where the powerful army, the self-appointed guardian of secularism, wields a strong influence in politics.

But his arguments have gone largely unheeded amid widespread support for early polls as an escape from the political uncertainty that resulted from his absence from official duties due to ill health and a government deadlock over democracy reforms required under Turkey's bid to join the European Union. The turmoil has come at a time of increased speculation that the United States could launch a military strike against Turkey's southern neighbour Iraq for its refual to allow UN inspectors to check its suspected arsenal of weapons of mass destruction. The scenario has raised fears in Turkey, a staunch US ally in NATO, which believes a war in Iraq would have dire economic consequences and upset fragile political balances in the region.

In a television interview late on Tuesday, Ecevit reiterated his concerns regarding an operation against Baghdad and said that Ankara was making the necessary military and political preparations. "That is why we are trying to dissuade the US administration from a military operation and we are trying to explain them that we will seriously contribute to peace in Iraq... without a need for such a military operation," he told the private ATV channel. There was speculation in the Turkish press Wednesday that a military strike against Iraq could force the postponement of elections under a constitutional article which stipulates that polls are delayed for a year in case of war.

Early polls themselves are in the meantime widely expected

to delay the adoption of a package of EU-required democracy reforms

submitted to parliament last week by the coaltion junior partner, the

Motherland Party (ANAP). ANAP wants the reforms to be passed before

polls in November, but chances are slim that MPs will participate in

what could be lengthy legislative work instead of electioneering. Turkey,

the laggard of all 13 EU-hopefuls, fears that it could be left out of

the Union's enlargement plans if it fails to secure a date for the opening

of accession talks by the end of the year. ![]()

2. - Newsweek - "Eyes On Turkey":

The government is collapsing. The economy is a mess. Voters are fed up. The stage is set for an Islamic party to take power. Should Europe—and the world—worry?

Aug. 5 issue / by Owen Matthews and Sami Kohen

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, head of Turkey’s most popular political

party and a devout Muslim, has something to hide—and it’s

in his refrigerator. At his home in a middle-class suburb of Istanbul

earlier this year, he stopped a Turkish TV crew from peeping inside

the fridge in his kitchen. “Private,” he declared. Just what

did Erdogan not want the nation to see? A few cans of beer, according

to an associate, kept on hand for thirsty guests.

WHY THE FUSS? Turkey is a firmly secular country. Though most Turks are Muslims, they’re still enthusiastic consumers of beer, wine and raki. Only the ultraconservative Islamic fringe has a problem with alcohol—the kind of people that Turkey’s secularist and politically powerful military wants to keep out of power. So when a politician whose party is topping the polls and looks like he might even rise to head a new government is embarrassed about having an un-Islamic can of beer in his house, Turkey’s secularists get a little nervous.

Should Turkey’s Western allies be worried, too? Turkey is heading for early elections in November, and the prospects for its mainstream political parties aren’t good. The country’s 77-year-old prime minister, Bulent Ecevit, is old and ailing, unable to lead a fractious coalition that threatens to dissolve at any moment. The economy, already a shambles, grows worse by the week. Popular disaffection runs so deep that the approval ratings of even Turkey’s largest traditional parties have sunk to 10 percent or less.

Contrast that with Erdogan’s newly formed pro-Islamic, conservative party known as Justice and Development. AK, as it’s known for short, enjoys a 24 percent rating—making it by far the leader of the political pack. As a popular former mayor of Istanbul, Erdogan is the new face in Turkish politics, untainted by the current government and economic crisis that no one else seems able to cure. And unless the military steps in to stop the AK’s meteoric rise, it looks like Turkish voters are ready to give Erdogan and his Islamic alternative a try.

At a time of jihad and the war on terror, when Islam is widely taken to be the enemy of modernity, that prospect might be expected to set alarm bells jangling, especially in Europe and the West. After all, Turkey is a key NATO ally, the likely launching pad for any assault on Saddam Hussein. And as early as December of this year, it might just finally be set to receive its long-sought invitation to join, at some point, the European Union. Could an “Islamic” Turkey set back these prospects?

If past were prologue, there might be cause for worry. Erdogan and many of the AK leadership were once Islamic activists in Turkey’s infamous Welfare Party, which briefly took power in 1996. It was Turkey’s only experience of an Islamic government—and it wasn’t happy. Islamist Necmettin Erbakan, then prime minister, suggested that Turkey head a union of Islamic nations. He visited Libya and built closer ties with Iran. Before long the Turkish military lost patience and deposed him in a constitutional coup in February 1997, banning the Welfare Party to this day. Erdogan himself spent four months in jail in 1999 for “inciting religious extremism,” when he read out a poem to a crowd in southeastern Turkey, allegedly inflammatory for linking military and religious themes. It was, ironically, an excerpt from standard grade-school textbooks: “The domes of the mosques are helmets / And the minarets are our bayonets.” He is also currently under investigation again after videos were released last year recording remarks he made in 1992, in which he appears to praise Islamic Sharia and criticize the Army’s role in politics.

Erdogan himself has a ready reply to such charges: that was then, and this is now. Like former communists in Eastern Europe, Erdogan claims that times have changed and so has he. His new AK Party isn’t “Islamist,” he told NEWSWEEK. It’s pro-religious freedom. Turks of every religion must be able to exercise their faith, as well as other basic individual liberties, he explains. “We are for democracy, secularism, justice and social welfare. We want to strengthen the constitutional system, not to destroy it,” he says, likening his party’s identity to that of a European-style “democratic conservative.” And that’s another important change. Once vehemently anti-Europe, Erdogan is now strenuously pro-Europe—so much so that the AK Party’s 53 members of the legislature recently lobbied to reconvene Parliament in order to pass EU-inspired reforms that would permit the nation’s Kurds to broadcast and teach in their own language and would ban the death penalty in Turkey.

It’s a remarkable evolution. Elsewhere in the world, Islamists often seek to squash individual rights. In Turkey, at least when it comes to the AK, they champion them—for an obvious reason. Turkey’s Islamic faithful have the most to gain from the kind of liberalizing laws suggested by the EU. Ever since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk founded the Turkish Republic in 1923, public expressions of Islam have been strictly controlled in a way unthinkable in modern Europe. Conservative women students, for instance, are not allowed to wear head scarves to school or university; if they do they are thrown out. State employees are forbidden from wearing “Islamic” beards and “un-contemporary clothing,” such as traditional Islamic shalwar pants or skullcaps. Friday sermons in mosques have to be approved by the state’s Ministry of Religious Affairs, and clerics (including priests and rabbis) are banned from wearing their ceremonial robes in public. “It is ridiculous. Turkey is 98 percent Muslim, yet we are less free to practice our traditions than Muslims in Paris or London or Berlin,” says Murat Yalcintas, the U.S.-educated deputy head of the AK Party’s powerful Istanbul branch. “This isn’t to do with religion,” he emphasizes. “It’s a human-rights issue.”

The AK Party has also shed the dour image of the former Islamist parties. The party’s spiffy, glass-and-steel headquarters in downtown Ankara could pass easily as headquarters for an investment bank. Energetic young people dash smartly hither and thither. Female staffers wear pantsuits, and no head scarves. It’s the young, college-educated generation, not some hidebound cadre of elders, that runs the campaign. AK has even accepted a sexy young Turkish woman pop star, Sevda Demirel, as a member.

Traditional Islamist voters, not surprisingly, disapprove. Among them is 48-year-old Bahri, a perfume-shop owner in Fatih, an ultraconservative area of Istanbul. Like many, he will vote for a more radical religious party, Recai Kutan’s Saadet, or Happiness Party. “AK has compromised,” he says, bearded and wearing a skullcap. “They are no longer righteous.” Such sentiments, widely shared among an older generation of religious conservatives, probably means that Erdogan is moving in the right direction. Religion alone, he recognizes, is neither a winning nor popular platform in today’s Turkey. Witness the foundering Saadet, which polls around 4 percent of the electorate. “The world has changed,” says Erdogan of his new post-Islamic image. “It is natural for us to change according to new realities.”

It’s a good shtick. The question is whether it’s entirely genuine. Many in Turkey’s military and bureaucratic circles, particularly, don’t buy Erdogan’s conversion. They fear that AK is a Trojan horse. Once in power, will it unleash a hidden Islamist agenda and institute reforms undermining Turkey’s secular order? “Do you want Friday to be an official holiday? Do you want a mosque in Taxim Square [in the heart of Istanbul’s secular nightlife district]?” asks the rector of a leading Turkish university, who requested not to be named. “This year it seems impossible; they will deny they want it. But next year it will be possible... All in the name of democracy, saying it’s what the people want.”

Erdogan himself shrugs off such concerns. Voters aren’t backing him because of his religious credentials, he repeats. They like his track record of political accomplishment and skills as a big-city manager, in stark contrast to the country’s current leaders. He was one of the most successful mayors in the history of Istanbul, before being jailed, and he clearly knows how to woo the grass roots. Local offices of the AK Party in Istanbul run neighborhoodwide employment agencies. They organize complaints to the local council, run programs for the disabled and sports tournaments for the young. They even distribute free AK Party footballs on weekends to picnickers—the kind of simple but effective electioneering that no other party has managed to pull off. “We saw Erdogan in action as mayor, and he did a good job,” says Kerim Zengin, a former Democratic Left Party councilor in the Istanbul district of Gaziosmanpasha who recently switched to the AK Party. “We don’t trust politicians anymore; we look only at results, not words.”

The acronym “AK” means “white” or “pure” in Turkish, and much of Erdogan’s support rests on the untainted image of his party. So far, it’s been spared the almost universal sense of disgust and distrust among voters for Turkey’s political class, which suffers a dearth of new faces. Erdogan’s campaign formula—coupling pro-European policy with a traditionalist, religious twist and an emphasis on honest government—seems to have caught the mood of the moment. But even as he has emerged as a player in Turkey’s high-stakes political game—and perhaps the player—there are wild cards in the deck that could produce some unpredictable turns of fortune.

One is Iraq, and whether an AK Party government would support a U.S. strike. Erdogan has been deeply skeptical—but so have most of Turkey’s mainstream parties, as well as the military. Some Turks fear that the AK Party may follow the example of the old Welfare government and try to forge stronger alliances with Arab neighbors at the expense of its ties with America and Europe. So far, there’s been no sign of that. AK members of Parliament have consistently voted to extend the U.S. use of the Incirlik air base to enforce the no-flight zone in northern Iraq, which must be renewed every six months. “If we see proper justification [for a U.S. strike], if it’s approved by the U.N., then OK,” says the AK Party’s deputy chairman, Abdullah Gul, following the line taken by Ecevit in meetings with U.S. Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz last week. “Otherwise we can’t justify this to our own people, or to our neighbors in the region.”

Another wild card is Erdogan’s relations with the Turkish military. However carefully the AK Party leadership treads, a clash between the party and the generals, the country’s de facto behind-the-scenes rulers, is almost inevitable. Erdogan has long argued that the military should have no role in government, and though he has lately toned down that rhetoric, AK Party activists haven’t. “We believe that all state institutions should do their own jobs,” says Yalcintas when asked about the Army—a near-blasphemy in secular Turkey.

Predictably, the Army and other strongly antireligious state institutions have been doing their best to shut Erdogan down. Recently a court ruled that his 1999 conviction bars him from being elected to Parliament, and therefore from becoming prime minister. Erdogan’s lawyers are appealing. But he’s also facing treason charges for criticizing the Army in 1992, and another criminal investigation has been opened for alleged corruption when Erdogan was mayor of Istanbul—an accusation that many find ironic since, at the time, Erdogan was famously (and unusually) uncorrupt, to the point of refusing even to live in the official mayor’s residence.

What the Army will do if Erdogan and his party win the election is unclear. His next court date isn’t until just before the probable Nov. 3 ballot, so he will be free during the campaign. Jailing him at his moment of victory would probably be hard to justify, even within the military. Apart from the outcry in Turkey, the EU’s Copenhagen summit is set for December. There, Europe will consider whether to set a date for formal accession talks for Turkey—and decide whether to accept Cyprus as a member, excluding the Turkish portion of the divided island. Denying a popularly elected leader his post on flimsy charges would not do Turkey’s democratic image much good and at such a critical juncture—and it could cripple its EU bid, which the Army strongly supports.

Erdogan’s opponents (and, again, especially the military) must also take account of his likely postelection partners. The best-case scenario would be that an AK government would be in coalition with respected centrists defecting from the current regime, among them former foreign minister Ismail Cem, who recently formed a new center-left party called New Turkey, and possibly Economy Minister Kemal Dervis and other center-right parties. That would be good news in the West, and especially for the International Monetary Fund, whose $16 billion bailout depends on Turkey’s adhering to strict economic criteria.

The bottom line, ultimately, seems to be heartening. Unless Erdogan is an Oscar-winning prevaricator, there’s nothing inherently scary about his party’s coming to power. On the contrary, any stable government, even with a moderately Islamic hue, could well enjoy the widespread support required to undertake the tough steps necessary to bring Turkey out of recession. The country could also end up moving toward Europe more rapidly than under the current coalition. Indeed, the AK Party’s agenda for human rights has much in common with Europe’s, which so far has been the major hurdle betweeen Turkey and the Union.

Such speculation is a bit premature, of course. But this

much can confidently be said. If Erdogan and the AK win in November,

and if the Turkish political establishment allows the party to take

power, Turkey will have shown itself to be a true democracy—one

in which even anti-establishment parties can get themselves elected.

For a country that’s long been doubted on this score, that would

a huge stride indeed. ![]()

3. - AFP - "Death toll rises to 52 in Turkish prison hunger strike":

ISTANBUL / 30 July 2002

A hunger strike by Turkish prisoners against controversial jail

reforms claimed its 52th victim Tuesday, a human rights group said.

Semra Basyigit, a 24-year-old woman detainee, died in an Istanbul hospital,

one year after joining the hunger strike, a member of the Human Rights

Association (IHD) told AFP.

Hunger strikers have been operating on a rotating basis, taking liquids with sugar and salt in them as well as vitamin supplements to prolong their lives. Basyigit was on trial for membership of the radical leftist Revolutionary People's Liberation Party-Front (DHKP-C), an outlawed group seen as the mastermind behind the strike.

The strike action was first launched in October 2000 by hundreds of mainly extreme left-wing inmates against the introduction of high-security jails in which cells for one to three people replaced large dormitories housing dozens. The protesters claim the cell system increases their isolation and leaves them more vulnerable to maltreatment.

The government has categorically ruled out a return to the dormitory system, arguing that it was the main reason behind frequent riots and hostage-taking incidents in the country's unruly jails. Support for the strike has faded in the face of the government's tough response. Only about 30 inmates linked to the DHKP-C are continuing their protest action, the IHD.

The anti-torture committee of the Council of Europe said last week Turkey had made progress in efforts to ease the isolation of the prisoners by allowing communal activities and open visits, but urged authorities to further relax the restrictions. The hunger strike death toll also includes outside activists who joined in solidarity with prisoners.

Apart from those who have starved themselves to death,

four prisoners burned themselves to death in support of the strike and

another four people died last November in a police raid on an Istanbul

house occupied by hunger strikers. ![]()

4. - The Baltimore Sun - "Selling out to set stage for an attack on Iraq":

WASHINGTON / 30 July 2002 / by Dusko Doder

Reports that the Bush administration is prepared to write off the

more than $4 billion that Turkey owes the United States could not be

a clearer sign that the president's plans for a "regime change"

in Iraq are moving into high gear.

Turkey is the one country whose support is crucial in that endeavor because no effective military action against Saddam Hussein is conceivable without the use of U.S. military bases on Turkish soil.

The Turks raised other, more modest financial demands, such as hastening the approval of a $228 million aid package the Bush administration had earmarked for them in the current fiscal year. Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, who had been dispatched to Ankara to negotiate the price for Turkey's participation in the planned assault on Iraq, saw no problem in meeting those demands.

Proper decorum was preserved. The Turks insisted that their conditions were not conditions at all; indeed, they were not linked to Iraq. Top Turkish officials said publicly that they question the wisdom of the U.S. desire to topple Mr. Hussein. Mr. Wolfowitz, for his part, pretended the United States was eager to help an old friend in need. As he put it, we want to help Turkey's recovery and promote its economic growth.

He took this a step further by endorsing Turkey's request for membership in the European Union, which is Ankara's most cherished political objective.

A credible case can be made that the removal of Mr. Hussein would be in everyone's interest; few doubt that the Middle East would be a safer place without him. At the same time, Mr. Wolfowitz's hand was conspicuously weak in light of the blunt reluctance of America's Arab friends to take part.

But in arranging the deal, the administration had to do something that is both disquietingly hypocritical and ugly: It jettisons some of America's cherished principles for the sake of expediency. Specifically, Mr. Wolfowitz assured the Turks that the United States was firmly opposed to any arrangements in which the Iraqi Kurds would gain a measure of political autonomy in a post-Hussein Iraq.

The Kurds are the world's largest ethnic group without a state of their own. They live on some 200,000 square miles - nearly as big as California and Pennsylvania combined - that covers northwestern Iran, eastern Turkey, northern Iraq and northeastern Syria. Western experts estimate their number at 25 million, about half of whom live in Turkey. They are not Turks, not Arabs, not Iranians, but they are Muslims.

Turkey denies the Kurds' existence, insisting they are "mountain Turks." About 30,000 died before a 15-year-long Kurdish insurgency in eastern Turkey was quashed in the early 1990s. Now the government is alarmed that the creation of an autonomous Kurdish entity across the border in Iraq might rekindle Kurdish aspirations in Turkey and elsewhere.

Iraqi Kurds account for 23 percent of Iraq's 18 million people. They have been terrorized by Mr. Hussein's aerial bombardments, poison gas and a deliberate destruction of their rural society. Since the 1991 Persian Gulf war, they have been in control of an area nearly the size of Arkansas in northern Iraq, protected by U.S. and British air patrols that enforce no-fly zones.

With about 50,000 lightly armed men but no heavy weapons, the Kurds are the only organized opposition to Mr. Hussein and his Sunni Muslim minority. The Sunnis, who account for slightly less than 20 percent of the population, have dominated modern Iraq's politics by suppressing the Kurds in the north and Iraq's Shiite Muslim majority (60 percent of the population) in the south.

Until a few months ago, some U.S. strategists had planned to cast the Kurds in a role similar to the one the Northern Alliance played in Afghanistan. This was inevitable since the Shiites are suspicious of any U.S.-led liberation of Iraq, saying Washington would be satisfied with another dictator representing the Sunni military elite.

In 1991, the Kurds rose up against Mr. Hussein after being urged to do so by the first President George Bush (who withheld military support, however). This time, the Kurds made it clear they want a firm commitment from the second President Bush before taking up arms against Mr. Hussein. They would not join any venture that failed to guarantee their security and their rights as equal citizens in "a federal, democratic Iraq."

Such a pledge, after Mr. Wolfowitz's visit to Turkey, will not be forthcoming.

Yet the sense that war with Iraq is all but inevitable now permeates the administration. It remains to be seen how this is going to play in the intra-administration debate, especially inside the Pentagon, where the Joint Chiefs of Staff have publicly weighed in against an ill-prepared Iraqi venture.

The chiefs dismissed a plan for the conquest of Iraq that was authored by a former terrorism adviser to the president. It envisioned a combination of air strikes and U.S. Special Forces attacks in coordination with local rebels, presumably the Kurds.

The plan by Gen. Tommy Franks, head of Central Command, that is before Mr. Bush calls for about 250,000 U.S. ground troops. But where would they be pre-positioned?

Pentagon generals routinely ask other prickly questions. Do we have an exit strategy? Will the military have to undertake yet another "nation-building" task in a country far more complicated than Afghanistan?

The real problem centers on the use of U.S. power in conflicts in which U.S. national interests are ill-defined. However desirable it may be, is the removal of Mr. Hussein worth the risks entailed in dispatching 250,000 young Americans to a hostile desert? Why has this president failed to line up the kind of coalition that his father assembled for the Persian Gulf war? Mr. Wolfowitz and his boss, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, have offered no credible answers so far.

This is not to suggest that nothing should be done about Mr. Hussein, in particular if he has indeed developed weapons of mass destruction. Mr. Bush's pre-emptive strike doctrine offers an alternative. The way to defeat America's enemies, he told West Point cadets recently, is to hit them first before they manage to "attain catastrophic power" to strike at us.

Mr. Bush would get considerable international support if the goal of any attack on Iraq were to de-fang a dictator who had used such weapons against his people and his neighbors. The United States possesses sufficient means to accomplish that without resorting to ground invasions.

But most Arabs, and most U.S. allies, see Mr. Bush as lacking both a legal mandate or compelling reason (such as the Sept. 11 tragedy) to force a regime change in Baghdad.

Dusko Doder is a Washington-based author and journalist.

![]()

5. - Newsday.com - "U.S. Should Bolster Ties to Turkey":

29 July 2002 / by Michael R. Hickok

Michael R. Hickok is an associate professor in the Department

of Warfighting at the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.

Turkish leaders are fond of describing their country as a bridge. Turkey, with its commercial center in Istanbul, straddles the continents, bringing Europe and the Mideast together.

Turkey, with its past in the Ottoman Empire, has also been the crossroads where European Christian culture, Islamic Arab-Persian heritage and Central Asian nomadic traditions have blended into the modern secular democracy that underpins the Turkish republic today.

Turks want to expand this metaphor by making the country the conduit for the oil and natural gas reserves from the Caspian Basin and, as a future member, by connecting the European Union to markets in the Mideast and former Soviet Union.

Yet, the three pillars holding up the modern Turkish bridge - democratic politics, economic growth, strong security institutions - are all under stress as the ruling coalition crumbles and national elections loom in November.

Political disarray, economic disasters and a recalcitrant military are nothing new for Turkey. These issues have individually cycled through the last five decades of Turkish history, marked by intermittent military coups designed to restore order to an unruly house. American diplomats and intelligence analysts describe Turks' ability to survive the unpredictability of Turkish party politics and high-inflation economy as the skill of "muddling through."

The visit to Turkey July 16 of Under Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, Under Secretary of State and former U.S. ambassador to Ankara Marc Grossman, and Supreme Allied Commander Europe Gen. Joe Ralston suggests, however, that the Bush administration is no longer sure whether the Turks' habit of flowing through crises will serve this time.

Wolfowitz told Turkish reporters "we did not come here asking for decisions." One hopes that American officials were in Ankara to check for structural integrity, and there are reasons to be concerned.

Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit has watched his fragile coalition fracture as his health deteriorated and legislative reforms essential for potential Turkish entry into the European Union alienated hard-line nationalists within his own government. He has been unwilling to give up power, and his weakness led to defections within his own Democratic Left Party - necessitating a call for early elections.

According to recent polls, two of the three parties in the current coalition government are unlikely to draw enough votes to win any seats in the next parliament. Turkish politics are moving away from the center toward extreme nationalism and socialist economic policies. Some of this drift is a response to an economic crisis whose magnitude has not been seen since the 1940s.

In the face of political and economic uncertainty, American leaders have usually turned to the strongly pro-Western Turkish military as the final guaranty for continued relations between Washington and Ankara. Even here there are cracks in the support.

The United States is pushing Turkey to back potential military operations against Iraq despite Turkish concerns about the security and economic impact of a new war. Turks look back on their cooperation in the Gulf War with mixed emotions.

Senior Turkish officers set out the price of assistance. Ankara wants $228 million to offset the cost of its troop deployment in Afghanistan, forgiveness of $5 billion in military debt, lifting of restrictions on weapons sales and more input into what a post-Saddam Hussein Iraq would look like. If Turkey is to be the bridge carrying America's attack on Iraq, the Bush administration was finally told what the toll would be.

The thing about bridges is that the two sides being connected are inherently more important than the span between them. Iraq, not Turkey, is the main policy problem for the Bush administration. Washington's interest in Ankara is limited to keeping the bridge open and not the fundamental structural integrity of the culture, economy and military that holds it up.

Turkish leaders need to find a new metaphor; bridges are meant to be stepped on and Turks deserve a better future than that.

Against the Taliban, the Bush administration used Pakistan

as a base for its operations, only belatedly discovering the economic

and political weakness that threaten to engulf its allies in Islamabad.

Before America turns its attention to Saddam, Washington should take

direct steps to secure its long-time ally in Ankara with substantial

economic and security support.Michael R. Hickok is an associate professor

in the Department of Warfighting at the Air War College at Maxwell Air

Force Base, Ala. ![]()

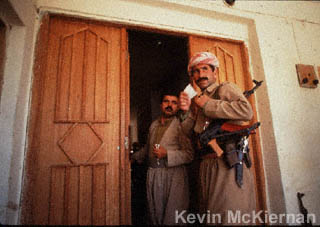

6. - AFP - "Iraqi Kurds set to seal agreement on implementing four-year-old peace deal":

ARBIL-IRAQ / 30 July 2002

The two main Kurdish factions sharing control of northern Iraq are

poised to seal an agreement on the implementation of contentious provisions

in a 1998 US-brokered peace deal, informed sources said here Tuesday.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) of Massoud Barzani and the Patriotic

Union of Kurdistan (PUK) led by Jalal Talabani are expected to announce

here Wednesday that they have agreed on "final formulas for resolving"

the remaining issues in dispute, the sources in this KDP stronghold

told AFP.

They described Wednesday's meeting as the "most important" in a series of meetings officials of the two sides have held to discuss implementation of the deal signed in Washington four years ago. The Hawlati newspaper, published in PUK-controlled Sulaymaniyah, said on Monday that the two parties had agreed to hold elections for a new regional parliament within six to nine months, "conditions in the area permitting", and to allow each faction to reopen offices in the zone controlled by the other.

The KDP and PUK often fought each other in the past for

predominance in the Western-protected enclave in northern Iraq, which

has been off-limits to the Baghdad government since the end of the 1991

Gulf War. But Barzani and Talabani agreed during a meeting in Germany

in mid-April to complete implementation of the 1998 peace accord and

pool their resources to combat Islamist radicals in the area. The KDP-PUK

rapprochement comes against the backdrop of US threats to launch a military

strike against Iraq and topple the regime of President Saddam Hussein.

![]()