27

August 2002

![]()

2. "Turkey’s Hangman Retires", Muslims debate the death penalty.

3. "Of Turks and Kurds", by WILLIAM SAFIRE.

4. "In Race to Tap the Euphrates, the Upper Hand Is Upstream", the Euphrates River is close by, but the water does not reach Abdelrazak al-Aween. Here at the heart of the fertile crescent, he stares at dry fields.

5. "In Turkey, it's the EU, stupid", Turkey's Nov. 3 election will shift the country's center of gravity closer to either the West or Middle East. While secular, progressive parties would accelerate the momentum for Turkey's entry into the European Union, a triumph of the Islamic-leaning party could dampen Europe's already tepid enthusiasm for the country's membership.

6. “Cyprus: handle with care”, Rarely has the European Commission played for such stakes. If it handles Cyprus's application deftly, it could bring peace to the island after half a century of disturbance.

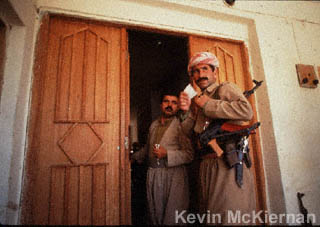

1. - IRNA - "Turkey fears US Iraq policy revives Kurdish independence":

ISTANBUL / 27August 2002

Against the background of a possible US military operation in Iraq

to unseat Saddam Hussein, tensions between Turkey and the Kurds of northern

Iraq are rising - and taking on a martial tone.

Relations between the two sides have degraded to the point where Iraqi Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani, in response to Turkish "provocations", warned that "a grave" would be prepared for the Turkish army if it dared intervene in northern Iraq, the dpa reported from Istanbul.

What is behind all the saber rattling?

US President George W. Bush's extensive efforts to include the Kurdish opposition in his plans to topple Iraq strongman Saddam Hussein have raised Turkish suspicions.

The idea of a change of regime in Iraq would find full support with Turkey's government and military, but only on condition that the creation of a Kurdish state be avoided at all costs.

After successfully overpowering the Kurdish Workers' Party (PKK) that for 15 years has sought to set up an autonomous Kurdish region in Turkey's southeast, Ankara is has no interest in seeing the unrest that could accompany the birth of a Kurdish state just across the border.

Despite its misgivings that military invention in Iraq would destabilize the region, Turkey has given the appearance of accepting a US attack.

"We are making political and military preparations," was the latest statement on the matter from Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit, who could not have ignored the financial benefits of a "strategic partnership" with the United States for his crisis-ridden country.

The first signs of Turkey's lack of trust for Iraqi Kurds appeared when Bush invited northern Iraqi opposition groups to Washington.

The Turkish army, as it pursued PKK fighters in Iraq, had made attempts to reach out to the Democratic Party of Kurdistan which Barzani led. When it came however to the Washington meeting, Barzani was forced to send a deputy because, as Turkish media reported, Turkish authorities confiscated his diplomatic passport.

At the heart of the matter, is Ankara's difficulty in swallowing Barzani's assertion that the Kurds of north Iraq have no plans of creating their own state.

This disbelief is strengthened by Turkish media reports that the two main Kurdish groups - Barzani's group and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan led by Jalal Talabani, who have shared power in northern Iraq since the 1991 Gulf War - have recently agreed to further consolidate Kurdish national structures.

The last straw was the discovery of a map of northern Iraq that Turkish media attributed to Barzani, in which the city of Mosul was identified as "Kurdish".

Turkish nationalists were immediately reminded of the disintegration of the (Turkish) Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 20th century.

"(The area around the cities of) Mosul and Kirkuk is a Turkmen area. That anyone has their eye on this region is intolerable," thundered Sabahattin Cakmakoglu, Turkish defence minister and member of the right-wing National Action Party (MHP).

According to the Turkish Daily News, there are three million Turkmen - ethnic Turks - in Iraq. Of that number, 400,000 live in the region around Mosul, which was already a subject of dispute at the end of the Ottoman Empire - not least due to the presence of oil there.

It was only under British pressure that Turkey relented

and ceded the territory in 1926 - to Iraq. ![]()

2.- National Review - "Turkey’s Hangman Retires":

Muslims debate the death penalty

26 August 2002 / by Amir Taheri

Before the summer is out Aleptekin Caqmaq will be out of a job.

Having sat idle in his office for 18 years, mostly doing crossword puzzles, Caqmaq has told journalists that he is happy to retire. Caqmaq is the official hangman in a high-security prison in Istanbul, Turkey. This month the Turkish parliament eliminated his job by abolishing the death penalty.

The historic decision removes the threat of execution from 49 prisoners, some of whom have been on death row since 1984, when then Prime Minister Turgot Ozal imposed a moratorium on capital punishment.

The Turkish decision has relaunched the decades-old debate on whether or not Muslim countries can do away with capital punishment.

A campaign to abolish the death penalty is already taking shape in Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim country, with tacit support from President Megawati Sukarnoputri. A petition calling for an end to capital punishment, signed by over 600 intellectuals, is attracting massive support throughout Iran, including among members of the Islamic majlis (parliament).

Capital punishment has already been suspended in a few predominantly Muslim countries, including Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Malaysia, with pressure building for outright abolition.

Campaigners for abolition also hope that a number of smaller Arab states, notably Oman, Qatar, and Bahrain may soon introduce at least a moratorium on death sentences.

Not surprisingly, opposition to abolition remains strong in the Muslim world.

According to most surveys, almost 70 percent of all legal executions in the world during the past two decades have taken place in the Muslim world. The overwhelming majority of those executed had been convicted of so-called "political crimes," which means opposing the regimes in place. In Iran alone at least 28,000 people were executed between 1979 and 2000.

Opposition to the abolition of capital punishment comes from both religious and secular elements in Muslim societies. Most secular groups, including the Turkish Nationalist Party, present arguments often used by opponents of abolition in the West, notably that the death penalty is a powerful deterrent against capital crime. Radical fundamentalists argue on less rational grounds, claiming that the idea of abolishing capital punishment is part of "a Jewish conspiracy" to deprive Islam of an "effective means of eliminating its enemies."

"Those who preach abolition [of the death penalty] would also oppose the fatwas needed to cleanse the earth from those who cause corruption on it," says Ayatollah Muhammad-Ali Shahroudi, the Iranian Chief Justice. "They are the same people who also condemn the heroic acts of Palestinians who commit suicide while wiping out large numbers of Zionist evil-doers."

More moderate religious groups argue that the death penalty is an integral part of the system of qissass (retribution) that is common to all three Abrahamic religions. What they miss is that qissass was designed to set the maximum — not the minimum — limits of punishment. The proverbial "eye-for-an-eye, tooth-for-a-tooth" is a symbolic way of saying that punishment must be proportionate to the crime, and should certainly not exceed it. In other words, if a member of your tribe loses a tooth in a fight with a member of another tribe, this does not give you the right to go and massacre all the members of the rival tribe. The most that you can demand is to break one tooth of the guilty man.

When it comes to the death penalty, even greater caution and circumspection are required. The mechanism under which a blood tithe (diyeh) is paid to the family of the victim is designed to obviate the need for putting the culprit to death.

Some religious scholars argue that although capital punishment is allowed as an extreme measure, its exercise is subject to so many rules as to make it impossible to use except in exceptionally rare cases.

Sadly, the Turkish decision came without a serious and genuinely popular debate at the national level. It was railroaded into legislation in the final session of a moribund parliament and as part of a complex package of economic and political reforms. Many of the parliamentarians approved the abolition because they supported other items in the package. And, Turkey is eager to gain EU membership, an impossible goal for a country that allows the death penalty. Whatever the motivation, the move is in line with the Turkish tradition of imposing long-overdue reforms from above.

Nevertheless, the Turkish decision has broken one of the taboos of the Muslim world and could open the way for a frank debate about capital punishment.

What is now needed is to explain the Turkish decision to the Muslim masses both in Turkey and throughout the Muslim world to ensure that long-overdue reforms, including the abolition of the death penalty, are not issues of concern only to Westernizing elites.

One issue that should be debated is a moratorium on all death sentences pronounced for capital "crimes." In fact, sentencing anyone to death simply because of his opinions and political activities is certainly anti-Islamic. There is nothing in Islam to give any government the right to murder its peaceful opponents. In time all states should abolish the death penalty, at least in the case of political "crimes."

Muslim public opinion may not yet be ready for an outright abolition of the death penalty. But it is certainly ready for a debate on the subject.

— Amir Taheri, an Iranian author and journalist,

is editor of the Paris-based Politique Internationale. ![]()

3. - The New York Times - "Of Turks and Kurds":

WASHINGTON / August 26, 2002 / by WILLIAM SAFIRE

Faced with a charge by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld last week that

Al Qaeda elements were in Iraq; And in light of detailed reports in

this space and elsewhere naming names of "Afghan Arab" terrorists

sent to assassinate Kurdish leaders who were captured by anti-Saddam

Kurds in northern Iraq; And aware that many of the terrorist captives

were revealing to interrogators their infiltration through Iraq, their

Qaeda training and their current production of poisons in mountain hideaways

— Saddam Hussein came up with an answer:

It's all an Iranian plot. Saddam's son Uday claims that those killers have nothing to do with either Al Qaeda or Iraq. The dauphin sought to divert the blame to a different end of the axis of evil.

That's a lie, of course, as the prisoners' interviews, papers and family backgrounds make plain. Tehran's murderous mullahs do not treat the Kurds as enemies because they are a thorn in the side of Iran's longtime enemy, Iraq — a fact underscored by Saddam's eagerness to shift the blame to Tehran.

But the "Qaeda connection" will not be the central reason we liberate Iraq. No evidence of Saddam's support of terror will convince the amalgam of today's McGovernites and yesterday's Bushies of the need to overthrow a dictator racing to acquire nukes. Final proof of close terror coordination will surface after the war, just as proof of Saddam's nuclear development stunned the complacent after the battle a decade ago.

More to the point is our ability to assemble regional power to back up our own. The Kurds and Turks have long been at loggerheads; only recently has Turkey granted members of its own Kurdish minority the rights to use their language and preserve their unique culture.

Key diplo-military question: How do we enlist and equip 70,000 pesh merga Kurdish fighters — and at the same time induce the powerful Turkish Army with its modern Israeli technology to join the liberation?

If, after air strikes, an allied force of American, British, Turkish, Kurdish and Iraqi Arab Shia came at Baghdad from all sides, Iraq's Sunni plurality would force Saddam to get on the cellphone to his Russian creditors to arrange asylum in short order.

But many Turks, having just defeated their own Kurdish terrorists headquartered in Damascus, are still transfixed by the chimera of Kurdish separatism. They worry that when Saddam is overthrown, Iraqi Kurds will split off into an independent Kurdistan, its traditional capital in oil-rich Kirkuk, which might encourage Turkish Kurds also to break away. But that defies all logic: would the Kurdish people, free inside a federated Iraq and with their culture respected in Turkey, start a war against the regional superpower?

Turks also worry about the million Turkomen in northern Iraq. It should not be beyond the wit of nation-builders to ensure that minority's rights and economic improvement. Turkey has a claim on oil royalties from nearby fields dating back to when Iraq was set up. As a key military ally in the liberation and reformation of that nation, and with judicious U.S.-guaranteed oil investments, Turkey should begin to get its debt paid.

America's primary purpose in assembling this alliance of peoples inside and outside Iraq is, plainly put, to stop a homicidal maniac and serial aggressor from gaining the power to threaten our cities with annihilation. A secondary purpose is to forcefully discourage any other nation from secretly supporting terror groups.

The third purpose is driven not by any lust for global domination, but by out-and-out Wilsonian idealism: we want to make the Middle East safe for democracy. And not just for Israelis, who have shown how self-determination feeds both body and soul, or just for Kurds, who have made their "no-fly zone" into an example of free enterprise and self-government for all Iraqis (and all Palestinians).

Old World-weary apostles of appeasement don't get it.

Deride it or not, America's self-protective action will also benefit

Arabs and Persians long repressed by monarchs and dictators and misled

by militant mullahs. Terrorists and their state sponsors are forcing

us to bring democracy to people who will discover that political freedom

is a force that empowers every human being. ![]()

4. - The New York Times - "In Race to Tap the Euphrates, the Upper Hand Is Upstream":

TELL AL-SAMEN, Syria / August 25, 2002 / by DOUGLAS

JEHL

The Euphrates River is close by, but the water does not reach Abdelrazak

al-Aween. Here at the heart of the fertile crescent, he stares at dry

fields.

The Syrian government has promised water for Mr. Aween's tiny village. But upstream, in Turkey, and downstream, in Iraq, similar promises are being made. They add up to more water than the Euphrates holds.

So instead of irrigating his cotton and sugar beets, Mr. Aween must siphon drinking and washing water from a ditch 40 minutes away by tractor ride. Just across the border, meanwhile, Ahmet Demir, a Turkish farmer, stands ankle deep in mud, his crops soaking up all the water they need.

It was here in ancient Mesopotamia, thousands of years ago, that the last all-out war over water was fought, between rival city-states in what is now southern Iraq. Now, across a widening swath of the world, more and more people are vying for less and less water, in conflicts more rancorous by the day.

>From the searing plains of Mesopotamia to the steadily expanding deserts of northern China to the cotton fields of northwest Texas, the struggle for water is igniting social, economic and political tensions.

The World Bank has said dwindling water supplies will be a major factor inhibiting economic growth, a subject being discussed at a weeklong international conference in South Africa starting Monday about balancing use of the world's resources against its economic needs.

Global warming, some experts suspect, may be adding to the strain. Droughts may be extended in already dry regions, including parts of the United States, even as wetter areas tend toward calamitous downpours and floods like those ravaging Europe and Asia this summer. In general, the world's climate may be more prone to extremes, with too much water in some areas and far too little in others.

Both the United Nations and the National Intelligence Council, an advisory group to the Central Intelligence Agency, have warned that the competition for water is likely to worsen. "As countries press against the limits of available water between now and 2015, the possibility of conflict will increase," the National Intelligence Council warned in a report last year.

By 2015, according to estimates from the United Nations and the United States government, at least 40 percent of the world's population, or about three billion people, will live in countries where it is difficult or impossible to get enough water to satisfy basic needs.

"The signs of unsustainability are widespread and spreading," said Sandra Postel, director of the Global Water Policy Project in Amherst, Mass. "If we're to have any hope of satisfying the food and water needs of the world's people in the years ahead, we will need a fundamental shift in how we use and manage water."

An inescapable fact about the world's water supply is that it is finite. Less than 1 percent of it is fresh water that can be used for drinking or agriculture, and demand for that water is rising.

Over the last 70 years, the world's population has tripled while water demand has increased sixfold, causing increasing strain especially in heavily populated areas where water is distant, is being depleted or is simply too polluted to use.

Already, a little more than half of the world's available fresh water is being used each year, according to one rough but generally accepted estimate. That fraction could climb to 74 percent by 2025 based on population growth alone, and would hit 90 percent if people everywhere used as much water as the average American, one of the world's most gluttonous water consumers.

Water tables are falling on every continent, and experts warn that the situation is expected to worsen significantly in years to come. On top of the shortages that already exist, the outlook adds to the tensions and uncertainty for countries that share water sources, like Turkey and Syria, where Mr. Aween is among those still waiting and hoping for the Euphrates to be brought to his door.

A Few Miles' Difference

The stories of Mr. Aween and Mr. Demir illustrate how the growing fight for water can make or ruin lives.

Until last year, Mr. Demir, 42, a father of nine in Turkey, was living an itinerant life as a smuggler and a migrant laborer. But on a recent scorching afternoon, he stood sunburned and content, his striped pants rolled above his knees, bare feet squishing in Euphrates mud.

"It seems like we have all the water we need," Mr. Demir said, leaning on his shovel and running a hand through his close-cropped hair. What has changed in this swath of southern Turkey is the arrival of irrigation. It is part of one of the world's largest water projects, an audacious $30 billion plan by Turkey's government to spread the Euphrates' gifts across a vast and impoverished region of the country.

By now, Mr. Aween, the Syrian, might have been celebrating, too. Under Syria's irrigation plan, ambitious in its own right, water from the Euphrates should have reached Mr. Aween's door, less than 50 miles from Mr. Demir's.

But strong doubts are emerging about whether the vast scope of Turkey's project will leave enough water for its neighbors downstream — so much so that Syria appears to have put the brakes on its development plan.

"We're still waiting," Mr. Aween, 40, said on behalf of his 2 wives, 3 children, and 17 brothers and sisters, who all live in a hamlet that bears the family name. He wore a loose, Arab-style outer garment and cheap plastic sandals as he hitched a rusty tanker trailer to a sputtering tractor, his water bearers. "But the water hasn't come."

The trouble over the Euphrates can be expressed in a simple, untenable equation.

As best as anyone can determine, the river, in an average year, holds 35 billion cubic meters of water. But the separate plans drawn up by Turkey, Syria and Iraq for building dams and irrigating fields would, taken together, consume nearly half again more water than the river holds.

Each country has acknowledged the impossibility of marrying their schemes. But none has shown any willingness to scale back. Trying to accommodate fast-growing populations and to head off a migration to the cities, each country is still clinging to its irrigation dreams.

On both sides of the Turkish-Syrian border, snapshots of those dreams still unfold on summer dawns, in fields that used to be good for little but grazing, but where new irrigation canals are now delivering Euphrates water in regular supply.

Thirsty crops like cotton and sugar beets have begun to thrive. Farm incomes have tripled. Young women who turn out in sparkling dresses tend prized plants with special care, shepherding the water down each muddy row. Young boys cavort in irrigation ditches that provide relief from the intense midday heat.

Now that there is water, Mr. Demir said, it would not be such a bad thing if his four sons, ranging in age from 4 months to 22 years, decided to stay and work the land — something he could not have imagined only a year ago when farming was far harder.

But in a world in which so much depends on having water, he bristled at the idea of sharing it. "If I used any less, the others would use more," he said. "I use what I need, and as for the rest, it's their business."

That kind of thinking has not helped Mr. Aween's village, not far from Tell al-Samen, where the absence of water is almost equally on display. With his family, Mr. Aween raises scraggly goats and grows whatever barley and wheat he can coax from dry, unirrigated land. It is a far cry, he said, from the lush green crops he would grow with irrigation — the difference between sustenance and comfort.

Syria and Turkey have been at odds since the late 1980's, when Turkey decided to proceed with its development project without consulting its neighbors.

To Turkey, the plan was an essential step in the country's development, a means of transforming an area that is home to six million people, including many restive Kurds, into a zone of greater economic and political stability. But to Syria, which depends on the Euphrates for half its fresh water, it continues to be seen as a major threat. Iraq, the far downstream neighbor, has been mostly a bystander because of its international isolation.

The basic disputes between Turkey and Syria — over water rights and allocations — would be familiar to any landowner who has struggled over competing claims to a stream or a well. But the fact that the parties are nations, with large armies at their disposal and large populations at stake, has added to the weight of the clash.

Less powerful militarily than Turkey, Syria resorted through much of the 1990's to indirect pressure, by giving support to the terrorist leader Abdullah Ocalan, the No. 1 enemy of the Turkish government. In response, Turkish officials sometimes went so far as to warn that the flow of the Euphrates into Syria could be cut.

Such talk has cooled in the last three years since the arrest of Mr. Ocalan. But the potential for trouble lingers.

Over the last year, as Turkey has completed many dams and has begun to extend its irrigation, the flow of Euphrates water into Syria has grown consistently smaller. The flow has fallen below levels allowed under Turkey's only existing commitment to Syria, an interim 1987 agreement intended for the period of dam construction.

Turkey has blamed drought and the overuse of the new, cheap water by farmers for the shortfall. The government says much of that can be reversed. But Turkish officials have also said they no longer see the 1987 deal as binding. The trend has raised deep concerns in Syria, which is already facing water shortages in Damascus, the capital.

Both countries say they are ready to strike a deal, but cannot imagine scaling back their development plans. "For half of Syria, the Euphrates is life," said Abdel Aziz al-Masri, a top official at Syria's Ministry of Irrigation.

Mumtaz Turfan, the director of Turkey's department of hydraulic works, echoed the sentiment. "Without our dams, life in Turkey would be impossible," he said.

Rising Tension, Dwindling Water

It has been a decade since Syria, Turkey and Iraq sat down to formal negotiations, and their positions remain as starkly opposed now as they were then.

Syria and Iraq want the water to be divided roughly in thirds. Turkey, on the other hand, claims more than half for itself. It says any sharing must take into account Turkey's status as the source of most Euphrates water and the home to a population that is half again as big as Iraq's and Syria's put together.

"I am sure that if we forget about borders, we can solve the problem," Mr. Turfan said. Over the last 30 years, he has presided over the construction of 700 dams in Turkey, and a map that stretches across his wall details plans for 500 more.

"I am providing water for 22 million people who take drinking water from our dams, and for 35 percent of our agriculture," he said. It would be a mistake, he suggested, for Turkey to accept less than the lion's share of the Euphrates. "Without irrigation, we can't do anything," he said. "We can't give it up and destroy our people."

Around the world, the question of water ownership has never seemed so divisive.

Despite efforts by the United Nations and others, the world has yet to come up with an accepted formula on how shared waters should be divided. That situation applies to nearly 300 rivers, including the Nile, the Danube, the Colorado and the Rio Grande, all subject to major disputes.

In 1997, a United Nations convention declared that international waterways should be divided reasonably and equitably, without causing unnecessary harm. But Turkey, along with China and Burundi, refused to sign the agreement, a sign of reluctance on the part of major upstream countries to cede their dominant positions.

Beyond current water shortages, one reason for the tension is a lack of optimism that pressures on the world's water supply might be eased.

Of course, some new technologies, including advanced irrigation techniques, innovative desalination methods and bold water-moving schemes, offer some hope.

But experts say the task of making fresh water available where there is none — from seawater, from icebergs or by moving surface water long distances — remains too costly to be widely adopted. Most easily accessible fresh water sources have already been tapped.

To those who would bend nature, there are many cautionary tales, including the Soviet-orchestrated drying up of the Aral Sea, an environmental catastrophe. Even for its project on the Euphrates, Turkey could not win World Bank support because of the plan's significant costs, including the submerging of an important archaeological site.

But sometimes, as in Turkey's case, the thirst for water is greater than any such opposition. Along the Euphrates, Turkey is paying its own way, despite the financial hardship and despite the uncertainty over how its plans will affect others.

In the dry heat of a Mesopotamian summer, how that tenacity is regarded depends on which way the water is flowing.

In an office in Al Raqqa, a Syrian city on the banks of the Euphrates, Iliaz Dakal, a consultant to Syria's land development agency, was studying a map of his own. It depicted, in vivid green, the land that Syria is already irrigating along the river. Much more land, though, like the fields that are home to Mr. Aween, was crosshatched to show uncertainty — its water and its fate now perhaps in Turkey's hands.

"For now, thank God, we have enough to grow the wheat we need," Mr. Dakal said. "But what about the future?"

Mr. Demir, in his muddy Turkish field, had an answer, saying he had come to see water as a byproduct of power.

"If Turkey is stronger," he said, "then

I get to keep my water." ![]()

5. - Washington Times - "In Turkey, it's the EU, stupid":

WASHINGTON / 27 August 2002

Turkey's Nov. 3 election will shift the country's center of gravity

closer to either the West or Middle East. While secular, progressive

parties would accelerate the momentum for Turkey's entry into the European

Union, a triumph of the Islamic-leaning party could dampen Europe's

already tepid enthusiasm for the country's membership. Incredible as

it may seem, the outcome of such a critical issue is being influenced

significantly by a battle of political egos.

The upcoming election will determine the makeup of parliament and who becomes Turkey's next prime minister. The Islamic-style Justice and Development Party is currently leading in polls, not because there isn't widespread support for secular, center-right and left parties, but because key players have been unable to strike alliances.

The first battle of wills emerged in July, when cabinet ministers exited en masse. Many wanted the ailing Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit to resign, while some sought a more prominent role in government. The resignations prompted parliament to schedule the election that was originally slated for April 2004 to be held in November. The ministers' exodus struck a fatal blow to Mr. Ecevit's political coalition, but this political shake-up could have led to political rejuvenation.

So far, though, it hasn't. Turkey's former foreign minister, Ismail Cem, created the New Turkey Party, and most Turks expected the widely popular former economy minister, Kemal Dervis, to join. But Mr. Dervis wisely opted out, since Mr. Cem has stubbornly refused to form a coalition with others, insisting his own party, with just 7.5 percent support, can win the required 10 percent of national votes necessary to win any seats in parliament.

Some observers claim U.S. requests for Turkish military bases for an invasion of Iraq have soured the popularity of pro-Western parties. But the Washington buzz over the Bush administration's reported war plans doesn't seem to have had an impact on Turkish politics — yet. "I haven't seen anything that can be directly traced back to talks about war in Iraq, probably because it has remained in the sphere of the hypothetical," said Stephen Blank, a national security expert at the U.S. Army War College. "But an actual war would create a lot of domestic uproar and repercussions all over the Mideast, not just Turkey." Mr. Ecevit has repeatedly voiced opposition to a U.S. invasion of Iraq.

Still, a triumph of the Islamic-leaning party wouldn't be as negative as it may seem. And despite the party's wide plurality support of about 19 percent, if it fails to win 276 seats out of the 550 in parliament, it will have to form coalitions to rule. The party is much more moderate than most Islamic parties around the world and supports Turkey's EU membership, as does a wide majority of the Turkish people. But the party wouldn't be as supportive of the economic and political reforms that Europe demands. And since many EU nations, such as Britain, see no urgency to Turkey's entry, a triumph of this party would seriously slow Turkey's ascension.

This would be an opportunity squandered —for Turkey, for Europe and America, too. Turkey's entry into the EU would give Westernized, progressive, free-market policies a foothold in the Middle East. Turkey's evolution would provide a critical example for many opportunity-starved Middle Easterners to observe.

While the Bush administration is juggling many foreign-policy

priorities right now, it must put Turkey's EU membership near the top.

Mr. Bush should lean on his European friends, particularly British Prime

Minister Tony Blair, to set a date for formal talks on Turkey's membership.

While the union can't be expected to usher Turkey in until it meets

the set criteria, it should demonstrate it does, ultimately, want Turkey

the join the club. ![]()

6. – The Telegraph – “Cyprus: handle with care”:

26 August 2002

Rarely has the European Commission played for such stakes. If it

handles Cyprus's application deftly, it could bring peace to the island

after half a century of disturbance. A moment of clumsiness, however,

and the Levant could topple into outright war.

To understand the danger, it is necessary to recall some recent history. When Cyprus became independent of Britain in 1960, a new constitution vested sovereignty jointly in the two communities. It was guaranteed by Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom, and barred Cyprus from uniting with any other country.

In 1974, after years of intercommunal violence, supporters of enosis - union with Greece - staged a coup with the backing of Athens. When Britain did nothing, Turkey, the other guarantor power, invaded and seized the northern third of the island as a safe haven for Turkish Cypriots.

Since then, the international community has recognised the Greek Cypriot regime as the legitimate government of Cyprus. The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is acknowledged only by Ankara.

Yet, in practice - and arguably also in law, since the 1960 accords insist on representation from both communities - there are two separate entities on the island. That is why it would be dangerous if the EU were to admit the whole island with the support of only one community.

Turkish Cypriots point out that the 1960 constitution, which the Greek Cypriot government still claims as the source of its legitimacy, forbids Cyprus "to participate, in whole or in part, in any political or economic union with any state whatsoever".

Many Turkish Cypriots see EU membership on the proposed terms as enosis by another name, and would almost certainly respond to it by seeking union with Turkey. This would bring the region closer to war than at any time since the 1970s.

There is, however, an alternative. Properly handled, the EU application could be used to bring the two communities together. Both sides have an incentive to deal. The Greeks want to be able to return to the homes from which they were expelled in 1974; the Turks want recognition. By the early 1990s, the outlines of a settlement were beginning to emerge.

Turkish Cypriots would withdraw from some territory in return for equal participation in a loose bi-zonal federation. Paradoxically, the EU's acceptance of the unilateral application destroyed the talks. Greek Cypriots believed that they would now get their way with or without Turkish consent, while Turkish Cypriots became angry and defensive.

Ten years on, a settlement on the basis of "land

for peace" is still feasible - but only if the EU makes such a

deal a condition for admission. Allowing in a divided island - something

that the Greek Government is loudly demanding - would be in the interests

of neither the EU nor Cyprus - and, not even, in the long run, of Greece.

![]()