6

September 2001

![]()

2. "Turkey's anti-corruption drive claims another senior victim", Turkey's anti-corruption drive, a key element in an IMF-backed economic recovery plan, claimed another senior victim Wednesday as Housing and Civil Works Minister Koray Aydin resigned over a probe into alleged large-scale fraud in his ministry.

3. "Kurds alarm over 'smart sanctions'", in the third of four features on Iraq's Kurdish region, BBC journalist Hiwa Osman examines the implementation of the UN oil-for-food programme and the Kurds' views on so-called smart sanctions.

4. "Turkey, Greece and the US in a changing strategic environment", the US has a stake in the evolution of Greece and Turkey as 'pivotal' states-pivotal because what happens there involves not only the fate of two longstanding allies (with NATO security guarantees) but also influences the future of regions that matter to Washington.

5. "Turkish Cypriot leader shuns UN initiative", Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash has rejected an invitation by United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan to visit New York for a renewed effort to resume talks with Greek Cypriot leaders.

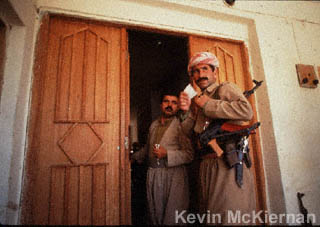

6. "The Kurds: a fragile spring", the UN has just prolonged the oil for food agreement with Iraq for five months, further profiting the Kurdish area under international military protection. But the Kurds' chance to reconstruct their world may be brief.

1. - Kurdish Observer - "HADEP Chairmen arrested":

4 HADEP district chairmen and a member of provincial executive

committee who has been detained on the grounds of the September 1 observation

were arrested in Istanbul. And in Amed nobody can get information on

the situation of HADEP administrators under detention.

4 HADEP district chairmen and a member of provincial executive committee

who have protested against the ban on the meeting to be held in Ankara

for the World Peace Day and have been detained were arrested. And it

has been learned that information can not be get about HADEP administrators

under detention.

More than 200 peace-lovers including HADEP administrators who were detained between August 21 and September 2, 2001, were brought before the court after their statements being taken at Zeytinburnu and Fatih chief prosecution offices. HADEP Sultanbeyli District Chairman Kudbettin Usenc, Umraniye District Chairman Yusuf Filizer, Uskudar District Chairman Bilal Algunerhan, Zeytinburnu District Chairman Zulfu Yasa and member of provincial executive committee Irfan Calis were arrested and put into Metris Prison on the grounds that they violated the law no 2911 on meetings and demonstrations.

On the other hand in Amed 26 people who were detained

on raids on August 30 and 31 nights were freed whereas more than a hundred

people who were detained on police assault on September 1 are still

under detention. No information has been get about HADEP administrators

under detention. A statement released by HADEP provincial organization

said that in case that there is no information their lawyers would resort

to legal ways. ![]()

2. - AFP - "Turkey's anti-corruption drive claims another senior victim":

ANKARA

Turkey's anti-corruption drive, a key element in an IMF-backed economic

recovery plan, claimed another senior victim Wednesday as Housing and

Civil Works Minister Koray Aydin resigned over a probe into alleged

large-scale fraud in his ministry. Aydin's move echoed that of former

energy minister Cumhur Ersumer, who quit in April amid harsh public

pressure following an investigation into suspected graft in multi-million-dollar

energy tenders.

The three-way government of Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit has pledged to eradicate chronic corruption in the country, seen as a core reason behind economic woes that culminated in a devastating financial crisis in February. Ankara is now implementing a strict program of economic reforms, including weeding out fraud, with a multi-billion-dollar aid package from the IMF and the World Bank. The embattled financial markets, meanwhile, have exerted strong pressure on the government not to deviate from its pledges, and have tumbled alarmingly at the slightest sign of an economic or political snag. Financial players hailed Aydin's resignation Wednesday.

"It shows that the economic crisis has given ministers accused of corruption the reflex to resign and this is reassuring for the markets," Sinan Akinman, an analyst with Garanti Securities, told AFP. Asaf Savas Akad, an economy professor and media commentator, said the economic crisis had increased public awareness about corruption. Aydin said he was quitting both his ministerial post and his parliamentary seat to facilitate the handling of the probe into his ministry, which was disclosed on August 22. The investigation focuses on alleged collusion between ministry officials and contractors over the past decade to ensure that favored firms won contracts at inflated prices.

"I am resigning from my posts of minister and parliament member in order to be an example to all Turkish politicians ahead of a thorough examination of all fraud allegations against my ministry, regardless of how high the probe will reach," he said in a live interview with the all-news NTV channel. Aydin charged that the probe and harsh media pressure on him to quit were part of a campaign aimed at tarnishing his party, the far-right Nationaliist Movement Party (MHP), which based its 1999 election campaign on a promise to conduct clean politics. Several dozen people, including ministry officials and contractors, have been detained during the probe but have not yet been formally charged. The media has accused Aydin of personal involvement in the fraudulent allocation of tenders, including a major project to build about 42,000 homes for victims of Turkey's two devastating earthquakes in 1999.

Aydin, who was a contractor before entering government,

has also come under severe criticism over the activities of construction

companies run by his relatives. He became the fifth minister to step

down since the February economic shake-up, which erupted when an unprecedented

public row between Ecevit and President Ahmet Necdet Sezer over ways

to fight corruption led to a breakdown in confidence on the volatile

markets. Since coming to power in 1999, Ecevit's government has carried

out nationwide anti-fraud operations in many realms -- from drug-trafficking

to customs, from energy tenders to fraudulent exports. But critics say

the government has failed to expand the probes when they have threatened

to reach high state echelons in a bid to protect its ministers and preserve

its fragile trilateral balance. ![]()

3. - BBC - "Kurds alarm over 'smart sanctions'":

In the third of four features on Iraq's Kurdish region,

BBC journalist Hiwa Osman examines the implementation of the UN oil-for-food

programme and the Kurds' views on so-called smart sanctions.

Iraqi Kurds were anxiously glued to their TV screens when the UN

Security Council began discussing the lifting of the embargo on Iraq

and replacing it with "smart sanctions".

Baghdad argues that sanctions are the sole reason for the misery of the Iraqi people. But the Iraqi Kurds have a different experience.

In 1996, the humanitarian situation was deteriorating rapidly as the sanctions imposed in 1991 began to bite hard.

The UN introduced the oil-for-food programme as a temporary measure. Iraq would sell some of its oil with the revenue to be used by the UN to provide the Iraqi people with food and medicine and to restore the infrastructure.

Food basket

Despite all the complaints about the programme, the Kurdish region is undergoing steady development.

The region receives 13% from the proceeds of the oil sale. A monthly food basket of 10 items and free healthcare are given to the people.

Previously, a whole family's salary was spent on food and medicine.

Shafiq Qazzaz, a minister in the Arbil Government, said: "I would like the oil for food programme to continue forever, but all good things come to an end."

According to a UN report published last year, the child-mortality rate in the Kurdish region is lower than before the sanctions. But the figures have almost doubled in the rest of Iraq.

The reason for this discrepancy between the Kurdish north and the rest of Iraq is that the UN directly implements the programme in the north with the co-operation of the Kurdish authorities.

In addition to providing security, the Kurdish authorities have mobilised their civil service to help the various UN agencies in their work. "We can truly claim that we have contributed to the relative success of the programme," added Mr Qazzaz.

Infrastructure in the Kurdish region was largely destroyed by Baghdad's 30-year war with the Kurds and the whole rural population was removed into collective towns near the big cities.

After the Gulf War, the Kurds returned to their villages. But rebuilding 4,000 villages and removing approximately 10 million mines was not an easy task.

A portion of the programme's funds is allocated to rebuilding the region's civil infrastructure. Various UN agencies and non-governmental organisations implement projects for electricity, water supply, sanitation, agriculture, health, education and mine clearance.

Kurdish grievances

Despite its success in the field of rehabilitation, the Kurds have many complaints about the programme.

The Kurds were not consulted or recognised as an authority

in the area when the programme was first introduced after an agreement

between Baghdad and the UN.

Projects implemented in the Kurdish region have to go through Baghdad.

But the Iraqi Government has been blocking many projects and preventing

international experts from entering Iraq.

The 13% share generated about $5bn for the Kurdish region. Baghdad's obstruction and UN bureaucracy have held back approximately $2bn.

Prior to the programme, farmers cultivated their land and sold the crops. But now, since food is being bought from outside, local produce has lost its value and farmers have lost motivation to cultivate their land.

"The UN should decrease the money spent on food and medicine",

said the Prime Minister in Arbil, Nechirvan Barzani. "They should

implement income-generating projects so that our people can rely on

themselves."

Kurdish economy

Trucks hauling goods and fuel to and from the region generate large sums of revenue and create many business opportunities.

The region's mini economic boom is clearly evident in

the stable exchange rate of the local currency.

The Kurds in the north use the pre-1991 Iraqi dinar ($1=17 dinars);

whereas in Baghdad, new dinars are printed to pay salaries. A 'Kurdish

dinar' now equals 100 new Iraqi dinars.

The recent talks of so-callede smart sanctions are creating

anxiety amongst the Iraqi Kurds.

The proposed system aims to clamp down on unofficial oil trade and this

will have a direct impact on the Kurds' economy.

The Kurds have asked to be compensated for the loss they will sustain, should smart sanctions be implemented. But it will not restore their situation to its current one.

Nechirvan Barzani said: "They might compensate for

our inability as a government to pay our employees' salaries but what

about all the small businesses that rely on this trade route?"

![]()

4. - Turkisch Daily News - "Turkey, Greece and

the US in a changing strategic environment":

The US has a stake in the evolution of Greece and Turkey as 'pivotal'

states-pivotal because what happens there involves not only the fate

of two longstanding allies (with NATO security guarantees) but also

influences the future of regions that matter to Washington. This gives

the United States a stake in Turkish prosperity, stability and convergence

with European norms.

Washington looks to Athens and Ankara to play a positive role in regional security and development, whether in the Balkans or in relation to energy security or missile defense. This includes the continued positive evolution of the Greek-Turkish relationship. A return to confrontation would negatively affect U.S. bilateral interests as well as NATO interests.

Turkish economic recovery and stability are preconditions for progress on many of the issues raised in this analysis, and should be strongly supported. Since Europe is already structurally engaged in the Greek-Turkish equation, and the U.S. has a stake in deepening this engagement, a U.S.-led approach is inappropriate. Similarly, the parties themselves must take the initiative in further developing Greek-Turkish relations.

The U.S. should recognize that Turkey's prospects for full EU membership remain mixed at best. Convergence rather than membership is the real objective from the perspective of U.S. interests. Washington should press its European partners to adapt their plans for ESDP to give Ankara a greater role in European decision making on defense-or at least to broker a compromise that will avoid a Turkish break with Brussels and the risk of paralysis over European-led initiatives at NATO.

On Cyprus, the goal of a 'bi-zonal, bi-communal federation' remains appropriate. The U.S. can have a role, but not necessarily the leading role, in any settlement arrangements for the island. Cyprus is increasingly an EU-led issue, and the key incentives for compromise will come from Brussels. If Cyprus is offered EU membership against a background of tense Turkish-EU relations, we should be prepared for a strong Turkish political reaction.

Ian O. Lesser

Outlook for Aegean Detente

There has been substantial improvement in the relationship between Athens and Ankara. Both countries have a strategic interest in better relations. But the rapprochement remains tentative and subject to reversals, and the core issues of Cyprus and the Aegean remain unresolved. Three years ago, Greece and Turkey were still engaged in a dangerous game of brinkmanship, with a daily risk of accidental conflict and escalation. Bilateral frictions impeded the completion of new NATO command arrangements for the eastern Mediterranean and threatened the cohesion of the Alliance. Through successive Balkan crises, U.S. policy has stressed the risk that regional conflict could spread to Greece and Turkey and reinforce "civilizational" cleavages in the region, a theme reiterated in the context of Kosovo and Macedonia. In fact, Athens and Ankara have taken a cautious, multilateral approach to the Balkans, and cooperation in Balkan stability and reconstruction was one of the few bright spots in Greek-Turkish relations prior to 1999.

Much has been made of the "earthquake diplomacy" accompanying the 1999 disasters in both countries. These events had a significant effect on public opinion and helped to overcome the overheated nationalism that has prevailed at times on both sides of the Aegean. But the real significance of the earthquake diplomacy was the scope it gave to policy makers in Athens and Ankara already committed to detente for strategic reasons. Foreign Ministers Ismail Cem and George Papandreaou have been instrumental in this change of course. Despite considerable support, especially from the private sector in both countries, they are keenly aware of the need to proceed carefully in deepening Greek-Turkish reconciliation. To date, a series of meetings, including high-level visits, has produced nine bilateral cooperation agreements covering peripheral but significant matters, from tourism to counter-terrorism. A package of confidence building measures has been agreed, and is ready to be implemented under NATO auspices. For the moment, the core issues of Cyprus and the Aegean have been left aside, but it is now clear that these very divisive issues must be addressed in some form if the current is to be consolidated and extended.

Over the longer-term, the prospects for detente will be heavily influenced by the character of Turkish-EU relations. Europe is central to the strategy of rapprochement for both countries. Friction between Ankara and Brussels would reduce the incentives for bilateral cooperation, and could encourage a more nationalistic and less conciliatory mood.

What Are U.S. Interests? What is at Stake?

This background suggests that U.S. interests are engaged

in important ways:

The United States has a stake in the evolution of Greece and Turkey

as "pivotal" states-pivotal because what happens there involves

not only the fate of two longstanding allies (with NATO security guarantees)

but also influences the future of regions that matter to Washington.

This gives the United States a stake in Turkish prosperity, stability

and convergence with European norms.

Washington looks to Athens and Ankara to play a positive

role in regional security and development, whether in the Balkans or

in relation to energy security or missile defense. This includes the

continued positive evolution of the Greek-Turkish relationship. A return

to confrontation would negatively affect U.S. bilateral interests as

well as NATO interests.

The United States wants Greek and Turkish policies to contribute more

specifically to U.S. freedom of action in adjacent regions. On the diplomatic

front, this includes support for U.S. policy aims in relation to both

crisis management and reconstruction in the Balkans, as well as to the

containment of Iraq and Iran. In security terms, it includes predictable

access to Turkish and Greek facilities for regional contingencies and

flexibility to engage or hedge in relations with Russia, as appropriate.

Policy Options

Approaches to furthering these objectives differ principally in terms of the extent of U.S. engagement and the question of policy leadership. Given NATO commitments and the strong nature of U.S. interests in Turkey and Greece, disengagement is not a viable option. On at least some important questions, however, it is reasonable to ask whether the United States, Europe, or the parties themselves should take the lead.

A - Focus on bilateral approaches, and provide a lead from Washington. This is the traditional course. It acknowledges the resonance of these issues, including the Cyprus question, in U.S. domestic politics. In the current environment, it can also reassure regional allies, above all Turkey, that the United States is not disengaging from European affairs. Moreover, the United States will have an independent stake in shaping regional diplomacy and security in ways that accord with U.S. interests. The issue of access to Incirlik Air Base, for example, is not of central interest to Washington's European allies, and we may not wish to see Turkish attitudes toward Iraq or Iran further "Europeanized." U.S. leadership may also help to ensure that Turkish-Greek relations remain in balance-something that might prove difficult without U.S. advocacy on Ankara's behalf. Cyprus diplomacy would be a key test of the viability of this approach. Certain initiatives, including the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline, arguably will not happen at all without active U.S. leadership and support.

B - Let Europe take the lead. This approach would acknowledge Europe's increasingly central place in the outlook of both countries. The United States has been a beneficiary of this trend, and may wish to support it. Moreover, the Helsinki summit has made the EU role a permanently operating factor in relation to Turkey, the future of Cyprus, and the Aegean dispute. Improved relations with Brussels provide an incentive for all sides and will be critical to the deepening of Greek-Turkish detente. The United States should welcome an opportunity for some of the diplomatic and burden to shift to Europe, especially with other claims on U.S. attention. In the context of relations with Turkey, a more balanced transatlantic approach can take pressure off of otherwise contentious issues between Ankara and Washington. The United States has pressed for a greater Turkish role in Europe, and it should now take the next steps to encourage it. In the case of Greece, as recent experience suggests, the less bilateralism, the better.

C - Let the parties solve their own problems. This option pertains, above all, to the question of how to strengthen Greek-Turkish detente. Both parties are sensitive to the appearance of being pushed into further concessions against their national interests. An arms-length approach from Washington could be helpful here. The same might be said of the EU, but Europe, post-Helsinki, is a structural participant in the process and cannot disengage. At the end of the day, leaderships in Athens and Ankara must decide whether to move forward and how.

D - Refocus U.S. engagement to allow for a shift of roles. The overall thrust of U.S. policy toward these allies and their regional roles should change. We should capture the advantages of more European and multilateral approaches and take an arm's length approach where appropriate. At the same time, the United States and its partners should jointly redefine bilateral relationships to address new issues and foster more predictable partnerships. With some important exceptions, Washington should let Athens and Ankara manage the next stages of their reconciliation, and we should recognize that the key decisions and policies regarding Cyprus must come from Europe. Europe is also the leading factor in domestic change for both countries. Reminding Europe of its responsibility vis-a-vis Turkey should remain a feature of Washington's transatlantic policy.

Next Steps

Turkish economic recovery and stability are preconditions for progress on many of the issues raised in this analysis, and should be strongly supported. Since Europe is already structurally engaged in the Greek-Turkish equation, and the United States has a stake in deepening this engagement, a U.S.-led approach is inappropriate. Similarly, the parties themselves must take the initiative in further developing Greek-Turkish relations. On wider, regional issues, Greece and Turkey should be integrated in transatlantic strategies. Washington should stay engaged in policy toward Greece and Turkey, but should refocus its engagement toward the following priority next steps.

Encourage Turkish reformers and recognize the importance of strong support from Washington in restoring confidence in the Turkish economy. This should include continued backing for IMF-led financial assistance.

Continue to stress the importance of closer Turkish convergence with and integration in Europe. But the United States should recognize that Turkey's prospects for full EU membership remain mixed at best. Convergence rather than membership is the real objective from the perspective of U.S. interests. Washington should press its European partners to adapt their plans for European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP), to give Ankara a greater role in European decision making on defense-or at least to broker a compromise that will avoid a Turkish break with Brussels and the risk of paralysis over European-led initiatives at NATO.

On Cyprus, the goal of a "bi-zonal, bi-communal federation" remains appropriate. The United States can have a role, but not necessarily the leading role, in any settlement arrangements for the island. Cyprus is increasingly an EU-led issue, and the key incentives for compromise will come from Brussels. If Cyprus is offered EU membership against a background of tense Turkish-EU relations, we should be prepared for a strong Turkish political reaction. This possibility increases the importance of having effective Greek-Turkish risk-reduction measures in place.

Engage Greek and Turkish leaderships toward the development of a new, more relevant strategic agenda. For Turkey, key elements of this agenda can include energy security, ballistic missile defense, dealing with Russia, and integrating Turkey in Europe. Dialogue on a common strategic agenda can help to increase the predictability of Turkish defense cooperation, including access to Incirlik Air Base for Gulf and other contingencies. The United States should also consider exploring with Ankara new activities of mutual interest that could be conducted at Incirlik, looking beyond Operation Northern Watch. With Athens, new agenda discussions can usefully focus on Balkan reconstruction, security cooperation in the Adriatic, and possible roles for Greece in the Middle East peace process.

Offer tangible support for the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline. With the discovery of new proven reserves in the Caspian, there is a better chance for the pipeline to prove economic. To date, Washington has offered strong diplomatic support but little substantive backing for the pipeline, despite a clear strategic rationale. If it is serious about promoting energy security and Turkey's regional role, Washington should be prepared to contribute, together with the private sector, appropriate assistance and credits toward the pipeline's construction.

(*) Testimony Before the House International Relations

Committee, Europe Subcommittee, June 13, 2001

Ian O. Lesser is a Senior Analyst at RAND, specializing in Mediterranean

and strategic affairs. From 1994-1995 he was a member of the Policy

Planning Staff at the U.S. Department of State.

The perspective offered in this testimony is the author's and does not represent the views of RAND or its research sponsors.

The analysis is based on Ian O. Lesser, "Policy

Toward Greece and Turkey" (Discussion Paper), in Taking Charge:

A Bipartisan Report to the President-Elect on Foreign Policy and National

Security (RAND: Santa Monica, 2001). See also, by the same author, NATO

Looks South: New Challenges and New Strategies in the Mediterranean

(RAND: Santa Monica, 2000); and Zalmay Khalilzad, Ian O. Lesser, and

F. Stephen Larrabee, The Future of Turkish-Western Relations: Toward

A Strategic Plan (RAND: Santa Monica, 2000). ![]()

5. - BBC - "Turkish Cypriot leader shuns UN initiative":

Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash has rejected an invitation by United

Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan to visit New York for a renewed

effort to resume talks with Greek Cypriot leaders.

Mr Denktash said at a press conference that no offer had been made that would bring him back to UN-sponsored talks on 12 September.

His press conference was held minutes after the UN envoy to Cyprus, Alvaro De Soto, told reporters that Mr Annan had invited President Glafcos Clerides and Mr Denktash for separate consultations.

"The necessary foundation has not been established for us to attend any form of negotiations," Mr Denktash said.

Mr De Soto said Mr Clerides had accepted the invitation.

Divided since 1974

The Mediterranean island of Cyprus has been divided between the

Turkish community in the north and the Greek community in the south

since 1974.

In that year, Turkish troops invaded in response to an Athens-backed coup to unite Cyprus with Greece.

But the international community recognises only the Greek Cypriot administration's sovereignty over the whole island.

Our correspondent in Nicosia, Gerald Butt, says the last round of UN-sponsored proximity talks broke up without agreement last November and since then public statements from the two sides have indicated that they remain as far apart on basic principles as ever.

But Mr De Soto said the hope was that meetings in New York would signal a new and re-invigorated phase of the efforts to resolve the Cyprus problem.

The Turkish Cypriot leader has said in the past that he

wants his breakaway state of northern Cyprus given equal status as the

Republic of Cyprus before returning to any talks. ![]()

6. - Le Monde diplomatique - "The Kurds: a fragile spring":

The UN has just prolonged the oil for food agreement with Iraq for five months, further profiting the Kurdish area under international military protection. But the Kurds' chance to reconstruct their world may be brief.

by KENDAL NEZAN

Ten years ago the western powers decided to create a "protection

zone" to allow the return of some 2m Kurds who had fled to Iran

and Turkey to escape the massive Iraqi offensive against them. This

was based on United Nations Security Council resolution 688 adopted

in April 1991. The 40,000 square kilometre zone with its 3.5m Kurds

is protected by a multinational air force based in Turkey.

The West's primary aim was to reassure its Turkish ally, which was facing a destabilising influx of hundreds of thousands of Kurdish refugees from Iraq to provinces already affected by Turkey's own Kurdish problem. The initiative, which came three months after the end of the Gulf war, did not meet with resistance from Baghdad: the Iraqi regime withdrew its civil administration from three governorates in the protected zone - Duhok, Erbil and Suleimanieh - in October 1991 and stopped paying the salaries and pensions of employees who decided to remain there. However, the West, under pressure from Ankara, which feared the emergence of an autonomous Kurdish state, did not want to look after the population itself by setting up a specific administration or type of UN protectorate, as it did in Kosovo in 1999; nor did it encourage a proper regional Kurdish government.

The West's message was clear: once home, the Kurds would be protected from Iraqi army attacks but they would have to run their own affairs and rebuild their devastated country on their own. For the Kurds, worn out by 30 years of war, this was a formidable challenge: they would have to run a country the size of Switzerland, in which some 20 towns and 90% of the (5,000) villages had been demolished, whose economic infrastructure had been destroyed, agricultural land mined and inhabitants dispersed. Nearly 80% of the active population were unemployed. The Iraqi regime had also cut the Kurdish region from the national electricity grid and placed an embargo on petrol and fuel.

The Kurds had to improvise in this chaotic situation and use their imagination and staying power. The United Front of Kurdistan, representing the eight local political parties, took over regional government and organised elections for a Kurdish parliament. These took place on 18 May 1992. Massoud Barzani's Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and Jalal Talabani's Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) won 51 and 49 seats respectively, and the (Christian) Assyrian/Chaldean minority, which counts 30,000 people, won five seats. The other parties (communist, socialist, Islamist etc) did not reach the 5% barrier but, even without seats, collaborated with the government of national unity formed in July 1992.

The Kurdish political leadership hoped that the West would swiftly recognise this new democratic institution and give it financial assistance. Instead, it ignored it. Ankara, Damascus and Tehran, despite their various disagreements, all talked of the danger of a Kurdish state and held three-monthly meetings of their respective foreign ministries to "keep an eye on the situation in the north of Iraq". The United States, anxious not to displease its Turkish ally, gave no support to the Kurdish democratic experiment, and nor did the European countries.

The double embargo (Iraqi and international) and absence of a minimum means of functioning led to a painful failure of the experiment [1]. Squabbling over meagre customs revenues degenerated into armed clashes between the KDP and PUK in May 1994. The neighbouring countries added to the troubles. The clashes went on until 1997. Nearly 3,000 died and tens of thousands were displaced. Finally the two warring factions realised that neither could eliminate the other militarily and that, in any case, the regional players (Iran, Turkey and Iraq) needed to maintain a balance of power between them, which would preclude the dominance of a single Kurdish political party even if it were to win a military victory. A cease-fire was concluded in November 1997. An agreement between the two Kurdish leaders, Barzani and Talabani, signed in Washington in September 1998 under the aegis of the US secretary of state Madeleine Albright, marked the official end to hostilities and established the basis for peace negotiations.

Under the accord, Barzani won recognition of his victory at the May 1992 legislative elections and its implications for the formation of a transitional government whose task was to organise new elections. Talabani, for his part, won agreement that part of the customs revenues would go to his party. No fewer than 60 meetings have been held since then to smooth out difficulties between the KDP and PUK and bring their viewpoints nearer together.

Administrative decentralisation

Painfully, and despite themselves, the Iraqi Kurds embarked on another new experiment, a form of administrative decentralisation. The territory protected by the western powers has been divided into two, north and south, and is governed by two identical administrative bodies. In the northern region, far more prosperous and better run, there is a coalition government based in Erbil, led by the KDP, but with a third of its members coming from the smaller parties, minorities (Assyrian/Chaldean and Yezidi) and independents.

In this northern region, 70% of the destroyed towns and villages have been rebuilt. The road infrastructure has been restored and extended, and communications re-established. Nearly all children in the north are now at school. There are also two universities (Duhok and Salaheddin) which teach arts, sciences, medicine and law to 12,500 students. The courses are in Kurdish, Arabic and English according to subject; teaching at primary and secondary school is in Kurdish. Students have decent university accommodation, teaching staff earn $140 a month (seven times more than their Iraqi counterparts) and are provided with housing.

In the south, the PUK-run government also includes smaller parties and independents. The university of Suleimanieh has 3,500 students; and there are 1,677 schools (for 367,755 schoolchildren). Unlike in the north, primary school is not yet compulsory for all children.

The technical services (health, education, transport, energy) of the two administrations cooperate with each other. After education, health is the main priority. Services are free and the authorities have rehabilitated the hospitals, built new health centres and provided them with modern equipment, often acquired on the black market because of the embargo - which is also responsible for the poor quality of medicines reaching Kurdistan via Iraq or Turkey. Two police academies train personnel to assure security in the towns, and two other centres train former guerrilla fighters (Peshmerga) to transform them into professional armed forces. The Kurdish parliament is located in Erbil, as is the Kurdistan Appeal Court.

A cultural renaissance

This Kurdish renaissance is even stronger in the field of culture. People are trying, with great enthusiasm, to make up for lost time. Three daily papers and more than 130 weeklies and magazines are trying to assuage people's thirst for information and knowledge. They deal with all sorts of issues, literature, cinema, history, computer science. A dozen television channels offer a variety of programmes for different categories of viewers; two of them go out on satellite and are watched by all the Kurdish communities in the Middle East and in Europe. Parabolic antennae also allow people to receive the international channels forbidden in Iraq and Iran, but free in Kurdistan (where internet cafés are also multiplying).

Newspapers of all political persuasions, including that of the Baghdad regime, are on sale. The small Assyrian and Turkman minorities have respectively 14 and nine schools that teach in their own languages, as well as publications and radio and television broadcasts. Kurds of Yezidi belief, (wrongly) accused by their Muslim neighbours of being devil worshippers, are free to practice their religion and their places of worship are protected.

Women are playing an important role, in particular in speaking out against acts of violence by Islamist groups supported by Iran and against archaic customs (such as so-called honour killings of adulterous women). This is helping to create a growing climate of freedom. The combined effect of these various internal factors - as well as the wish to win the sympathy of western opinion - has led the Kurdish political system, originally based on the dominant party/state model common to the region, to evolve towards a pluralist democracy. Even so, the historic leaders of the Kurdish armed resistance are a long way from reconciling themselves to becoming ordinary citizens or simple elected representatives.

Autonomous Kurdistan is experiencing relative prosperity, largely due to funds generated by the application of UN resolution 986 (oil for food) [2]. It allocates 13% of the revenues from oil sales to three governorates in the Kurdish region under international protection. The use of the revenues is supervised by nine specialised UN agencies who identify and finance projects in health, education, housing, repair of infrastructures and provision of water to displaced peoples. A food programme ensures that the inhabitants of the Kurdish region receive the same food rations as the rest of Iraq.

The Kurdish administration is helping develop these projects, giving protection to the UN agencies and providing them with warehouses and technical facilities. The UN agencies finance and execute projects that have received the backing of Baghdad "in the name of the absent Iraqi government". But the procedure is long and complicated. A project frequently takes more than a year to receive financial authorisation; and some projects are turned down.

Since 1997 $4.9bn has been allocated to the autonomous Kurdish region: $3bn has been used, the rest will be released as projects are approved. This financial assistance, together with the enterprising spirit of the Kurds and an efficient administration, is beginning to produce results. The country has become a vast worksite for the manufacture of roads, schools, libraries, housing, stadiums, parks, factories etc. Living conditions are improving noticeably.

Stable Kurdish dinar

The Kurdish administration is financed mainly by customs duties on lorries transporting various commodities to Iraq from Turkey and Iran, and to a lesser extent by income generated by the protection of the Kirkuk/Yumur/Talik pipeline and from border trade, especially in petrol. In order to relaunch the local economy, the Kurdish authorities have turned their region into a type of free zone, providing the Iraqi and Iranian markets with a variety of products, starting with cigarettes. These sources of income provide the Kurdish administration, which employs more than 250,000 civilians and around 80,000 security staff, with a yearly budget of $230m. The Central Bank of Kurdistan watches over the Kurdish dinar, which is stable vis-à-vis the dollar ($1=18 Kurdish dinars) and is at present worth 100 times the Iraqi dinar.

It is the first time in more than a century that the Kurds have administered part of their historic territory for such a length of time. On the whole they are doing it well. This Kurdish spring is raising hopes among the 25-30m Kurds who live in Turkey, Iran and Syria. But the future remains uncertain. The oil-rich districts of Kirkuk, Sinjar and Khanaqin, with their population of 2m, remain under the rule of the Iraqi regime, subject to a policy of Arabisation. Kurds here live in extreme poverty made worse by widespread exodus to Europe.

Furthermore, the reconciliation between the two main Kurdish

parties is not complete. They collaborate, but not always in complete

harmony. Old demons still lurk. In addition, the bordering states with

their own large Kurdish communities still do what they can to destabilise

the Kurdish administration, despite its pledges of neighbourliness and

economic cooperation. Kurdistan could not survive without Anglo-American

air protection and the 13% revenue allocated by UN resolution 986. Any

revision of sanctions against Iraq must include guarantees of protection

and financial assistance for the Kurds. Without these, there would be

another humanitarian disaster that would bring this fragile Kurdish

spring to a premature end. ![]()