18

December 2001

![]()

2. "Teen Marriage Crackdown in Turkey", Preteen girls in bright, baggy pants and scarves loosely tied around their heads playfully joke with each other, one trying to push the other off the curb into a puddle.

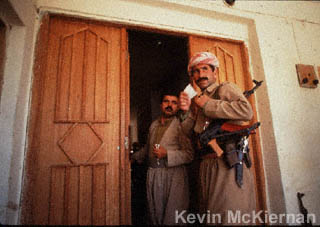

3. "The Other Iraq", in the safe haven of Iraqi Kurdistan, the Jews and Israel are remembered fondly, if increasingly vaguely.

4. "Baghdad Renews Contacts With Pro-Kurdish Tribes", the Iraqi government is trying to rally Kurdish tribes within areas under its control through largesse and other benefits.

5. "Turkish FM pledges support for new Afghan administration", turkish Foreign Minister Ismail Cem pledged his country's support for Afghanistan's interim administration Monday, committing Ankara to a key role in rebuilding a country ravaged by two decades of war.

6. "U.S. miffed by Turkey`s cooperation with Iraq", the United States is expressing unease with Turkey's continued economic cooperation with Iraq.

1. - The New York Times - " Turkish Hunger Strikers Risk Body and Mind":

ISTANBUL / by SOMINI SENGUPTA

Ismail Hakkisalic's memory is shot to pieces. He can read only a

few paragraphs at a time. He has great difficulty concentrating, closing

his eyes for several minutes as he struggles to form a sentence.

When he finally does, his speech is often chillingly childlike. "I wish for a world in which there is no torture," he said the other day, sitting on the floor of a damp, cold apartment he shares here with a number of his equally wasted comrades. "I wish for a world in which hands would only be used for handshakes, for rubbing each others backs."

For 129 days earlier this year, Mr. Hakkisalic was on what is known here as a "death fast," to protest the isolation of political prisoners like himself. The government said he was a member of a terrorist group.

Carried out mostly from inside the country's prisons by members of a half-dozen banned leftist organizations, the fasts have left dozens dead and hundreds disabled, and have gained macabre notoriety for being part of the longest hunger strike in modern times, with some fasters surviving more than 200 days.

Today, a full year after the death fasts began, no solution to the standoff is in sight. The government has not agreed to the strikers' demands - chiefly, to allow political prisoners to live in large communal dormitories, as they once did. The crowded compounds of the past, government officials say, became breeding grounds for terrorist organizations.

The hunger strikes have been carried out by members of a handful of marginal, mostly Marxist organizations, some of whom subscribe to armed struggle, some of whom agitate against the policies of the International Monetary Fund.

What unites them is their belief that confinement to cells that hold one to three prisoners, often with little contact with other inmates, is dehumanizing and that the new prison structure is designed to dismantle their very convictions by cutting off their interactions. They also say the new cells leave them vulnerable to torture by prison officials.

More than that, their cause is clearly an effort to shame a government with a spotty human rights record at a moment when it is struggling with issues about just how open a society it is willing to allow as Turkey vies for entry into the European Union.

Even though the death fasts have generated wide attention and protest marches in Turkey and abroad, the government has been largely unmoved.

It contends that it is too risky to let these groups operate unchecked inside the prison system. To do so, the director general of the prisons said in a statement, would "make it impossible for inmates to break ties with the terrorist organizations when they wish to."

A bill introduced in the Turkish Parliament last month seeks to prosecute those who encourage death fasts, with sentences of up to 20 years.

According to official figures, 154 prisoners are currently on hunger strikes; estimates of the number of hunger strikers outside prison, from a half-dozen to a dozen. Roughly 40 of the hunger strikers have died, according to rights groups here; prison officials say 24 have died in prison.

Outside, there are some 340 former death fasters who, like Mr. Hakkisalic, are now free and working to rehabilitate themselves.

After losing consciousness, Mr. Hakkisalic was taken to a hospital and released from prison on medical grounds in July. Since then, he has been eating, writing in his diary, exercising each morning - walking a straight line between two strips of masking tape in the hallway of this apartment.

At the moment, though, it is unlikely that he, or any of the hundreds of former hunger strikers who have made the drastic U-turn from starving to nursing themselves back to life, will ever again be whole.

The apartment Mr. Hakkisalic shares in a dense, working-class neighborhood is a gallery of determined self-destruction. One man trembles uncontrollably, as if from Parkinson's disease. Others, having lost their balance, have great difficulty with the simplest physical gestures - getting up from a sofa, walking a straight line. Most have lost a lot of hair.

Their eyes have a hard time focusing from one object to another. They can remember events from years ago, but not from yesterday. Most have lost the ability to produce new memories.

"It's almost impossible to bring them back 100 percent," said Dr. Onder Ozkalipci, a physician with the Human Rights Foundation here who supervises rehabilitation.

"Some of them were once leaders in their communities - teachers, intellectuals," the doctor said. Today, he said, they are like "plants."

Hunger strikers usually don't last more than 60 to 70 days. But the Turkish hunger strikers have developed new ways to stretch starvation. They keep the body's metabolism going with huge amounts of sugar - the equivalent of 60 sugar cubes a day - along with an average of about 12 glasses of water.

One woman, Oya Acan, who fasted for 200 days, was known to have kept up yoga practice for much of that time. She read three newspapers, wrote letters, spoke to her parents about what they would do after her release - all intended to maintain consciousness.

"I never believed I would die," a chain-smoking Ms. Acan, 42, who has spent eight years in prison for writing for a banned leftist newspaper, said the other day as she displayed a hollow-cheeked photograph of herself taken at the end of her fast. "I always thought there would be a solution."

But there has been no solution

A report by Amnesty International points out that while similar three- person cells exist elsewhere in the West, Turkish prisons severely limit the inmates' ability to come together for meals, exercise or study.

But a statement released by the director general of the Turkish prison system last week noted that inmates are now allowed to sign up for all manner of communal activities, from reading at the prison libraries to playing table tennis. Inmates sentenced on terrorism charges, the statement continued, have "chosen their own isolation."

In a report released last week, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture called on the Turkish government to appoint a mediator to resume talks between both sides. It also urged the government to lift provisions of its terrorism laws that restrict freedom of expression. "Criticism of the existing provisions concerning this freedom forms an important part of the backdrop to the hunger strike campaign," the committee said.

Meanwhile, the country's four largest bar associations floated a compromise last month to permit the inmates to socialize with one another in the day. The director general rejected the proposal, saying that to allow the inmates to interact in groups "would again lead to negative practices," including hostage taking and rebellion.

Of the 59,000 inmates in Turkey's prisons, nearly 8,600 are charged, like Mr. Hakkisalic, with a violation of the state's antiterror laws, according to a recent report by the state- run news agency.

Mr. Hakkisalic, the son of a military officer and a stay-at-home mother, was studying the solar system at Ankara University when he was seduced by radical politics, he says. He was imprisoned in 1995, on a charge of belonging to a terrorist organization. Why did he join the death fast?

"If they were going to strip us from our thoughts, from our identity, if their aim was to kill us that way, we told them here was our flesh and bones," he said, one slow word at a time, "But they couldn't take away our thoughts."

When he regained consciousness after 129 days of fasting, he says he has a vague recollection of waking up in a hospital room with intravenous tubes in his arms and his parents at his bedside. "The first thing I asked them was, `Does resistance still continue?' "

Yes, he was told, the fast continued in prison, but his had been ended.

He, like others who joined the fast, when asked if they really wish to die, say no. It's a tactic, they say, the only one they believe available to them.

If he really wished to die, Mr. Hakkisalic says, he could have killed himself much more easily than starving for 129 days. A death fast requires a devotion to the cause.

"The essence of the thing is decisiveness to the

point of death," he says, a finger pressing hard on his temple.

"It is actually a struggle for life." ![]()

2. - AP - "Teen Marriage Crackdown in Turkey":

ACARLAR / by SUZAN FRASER

Preteen girls in bright, baggy pants and scarves loosely tied around

their heads playfully joke with each other, one trying to push the other

off the curb into a puddle.

They could be girls from anywhere in rural Turkey - except that most are mothers and carry their babies wrapped in a bundle strapped to their backs.

It's a familiar sight in Acarlar, a small, close-knit town in western Turkey surrounded by olive groves and cotton fields where many of the girls are married off by the age of 14, some as early as 10.

``Anyone - boy or girl - still single by the age of 16 or 18 is considered to be left on the shelf,'' said townsman Burhan Pilar, 51. ``I took my wife at age 15 when she was 13.''

Authorities, concerned by the high rate of absenteeism in Acarlar's three schools, are now cracking down on teen marriages by rounding up husbands and fathers and fining parents when their children miss school.

The crackdown on teen marriages, illegal but tolerated for years, comes as Turkey vies for membership in the European Union Turkey recently increased the legal age for marriage to 18 from the previous 15 for girls, and made it mandatory for children to attend school through eighth grade instead of just fifth grade.

UNICEF also has called for an end to teen-age marriages, saying girls suffer physically and emotionally from early motherhood.

Measures taken in Acarlar have angered residents and have made this already closed community of about 9,000 more suspicious of strangers.

Police in the past two weeks have rounded up 40 Acarlar men, many still in their teens, whose brides are 14 or under. They face charges of having sex with underage girls.

The girls' families also are being investigated for possible exploitation of their daughters and could face three years in prison for having accepted money from the boys' families.

Local Gov. Kamil Koten has banned wedding ceremonies for underage girls, threatening restaurant owners with prosecution if they allow the use of their premises.

He has also imposed fines of $7 on parents for each day their kids miss school - a hefty penalty for the people of Acarlar, who work the fields and sell produce at markets around the province of Aydin.

The measures have worked, one principal said. Earlier, a third of the student body was absent; now, just a handful skips school among some 500 children, the principal said.

``God willing, a 200-year old tradition at Acarlar will come to an end,'' Koten said.

There is concern, as well, that the people of Acarlar are marrying from within their own community. It is not uncommon to see Acarlar children disabled from inbreeding, a local health official said on condition of anonymity.

The people of Acarlar say they feel betrayed by the town's officials.

``They came to our weddings, they drank our raki, they even danced with us,'' Ayhan Burak said. ``If it is illegal, they shouldn't have been there.''

Raki is a traditional Turkish alcoholic drink. The weddings at Acarlar are religious ceremonies carried out by imams, or religious preachers, and are not recognized by the strictly secular state.

``We are willing to change our ways ... we understand the dangers of young marriages,'' said Irfan Saka, whose 17-year-old son is in custody for underage sex. ``But you cannot expect us to cut our traditions away like with a knife.''

The men of the town agreed to meet with a reporter on condition that she leave the town soon after. They would not allow women or children to be interviewed. Residents have become weary of journalists after a front-page headline in the national Milliyet newspaper read: ``For sale by their fathers.''

Families here demand between $1,000 and $1,400 in ``bridal gifts'' or money paid by the bridegroom to the bride's family. Officially, such practices are illegal.

One young mother standing outside a grocery shop reluctantly gave her age, 16.

``She's 3. She's disabled,'' she said of her daughter, who was tied to her back with a large white cloth, before slipping away.

Although there are no official figures for child brides, the tradition also exists in other parts of Turkey and especially in the more traditional, mostly-Kurdish provinces of the southeast, where girls are sometimes forced to marry older men.

``Daughters are their fathers' properties until their wedding and then their husband's property after the wedding,'' said Nebahat Akkoc of the Diyarbakir-based women's group KAMER, which is also working to help stem teen marriages.

In Diyarbakir in southern Turkey, a women who asked to

be identified only as Fatma said she was 14 when her father forced her

into marrying a man she had not seen until her nuptials.

``(My father) said he'd lodge two bullets in my head if I refused,''

she said by telephone.

The people of Acarlar insist, however, that their daughters choose their

husbands and are never married off to much older men. ![]()

3. - The Jerusalem Report - "The Other Iraq":

Israel, Palestinians as seen from N. Iraq

Michael Rubin

In the safe haven of Iraqi Kurdistan, the Jews and Israel are remembered

fondly, if increasingly vaguely.

"THEY CALL That lack of restraint?" the former Iraqi army officer exclaimed, while watching the BBC's coverage of the Al-Aqsa Intifada on satellite TV last winter. "If this demonstration were held in Baghdad, there'd be 10,000 bodies in the street," said the Arab from Baghdad who now teaches in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Almost 4 million people live in the safe haven of northern Iraq. A de facto autonomous region, it has been administered by the Kurds since 1991 when Saddam Hussein withdrew his administration in a failed bid to embargo the insurgent Kurdish regions of the country into submission. The vast majority are Kurds, but there are also many Turkmans and Assyrians. In addition, thousands of Sunni and Shi'ite Arabs have taken refuge in the Denmark-sized haven, which was created by the United Nations and is protected by U.S. guarantees. They have either fled from Saddam's rule or surreptitiously sought employment in the safe haven, where the economy is better. Others simply come here to shop.

Though the region is run by the Kurds, they don't always see eye to eye with each other, and even fought a civil war from 1994 to 1996. Since it ended the two main parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), have basically divided the turf between their rival parliaments, working out of the cities of Irbil and Sulaymaniyah respectively.

Unlike the rest of Iraq, residents of the Kurdish-controlled north are free to speak their minds, without fear of retribution. And while the media across the Middle East portray a monolithic anti-Israel, pro-Palestinian sentiment, in this corner of Iraq the truth is quite the opposite.

When they see TV pictures of Palestinians marching through the streets of Hebron, Jenin, and Gaza waving portraits of Saddam, most Kurds feel anything but sympathy. "If the Palestinians love Saddam so much, why don't they try living under him; we'd be glad to move to Israel," comments a professor at the University of Sulaymaniyah. Many Kurds express outright disgust for Palestinian support for Saddam, a man they accuse of genocide.

Memories of the 1988 Anfal campaign are fresh in the minds of residents of northern Iraq. In a ten-month orgy of violence toward the end of the Iran-Iraq war, Saddam's forces murdered some 182,000 Kurdish men, women, and children. Saddam justified his brutal actions by accusing the Kurds of disloyalty during the war. His forces destroyed most of the region's towns and villages. The worst single atrocity took place on March 16, 1988, when the Iraqi air force dropped chemical weapons on Halabja, killing over 5,000 civilians.

THE IRAQI KURDS HAVE RISEN from the ashes of burned villages and destroyed communities. Much of their recovery is the result of the United Nations' so-called oil-for-food program, under which the U.N. funnels proceeds from Iraq's oil sales to humanitarian programs. New schools are apparent in the smallest villages, roads are being repaired and the major cities boast new sewers.

Though the program covers all of Iraq, Saddam appears

to have invested more of his portion of the income in the military and

new palaces than in reconstruction.

The north's economy also benefits from the fact that the Kurds use an

older issue of Iraqi dinars than the rest of the country, avoiding the

inflation caused by Saddam's unlimited printing of bank notes in Baghdad.

The old notes are worth 100 times as much as Saddam's dinars.

As for the Kurds' distaste for Palestinians, a case in point came in 1999, when the Jordanian director of UNICEF in northern Iraq decided to replace Swedish early childhood education specialists with Palestinians from UNRWA. The local population protested and, according to sources in the non-governmental organization community, UNICEF had to reverse the decision because of the "psychological trauma" the presence of Palestinians caused among Kurds whose families had been subject to Saddam's chemical weapons.

But the Iraqi Kurds' sympathy toward Israel is not simply shaped by their antipathy toward Palestinians. While the Kurds now acknowledge that independence is not an option in their part of Iraq, let alone pan-Kurdish unity with their brethren in Turkey, Syria or Iran, they view Israel as a model of a minority establishing control over its own future. Indeed, in 1967, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, father of the current KDP leader Masud Barzani, visited Israel for consultations with Moshe Dayan, among other government officials. The Kurds hoped for and received some training and equipment, but the flirtation did not last. Instead, the Kurds turned to the Shah's Iran, which could provide them with material assistance more directly.

Today, there remains considerable admiration for Israel, but high-ranking politicians in both the KDP and Jalal Talabani's PUK stress that the neighborhood in which they find themselves -- sandwiched between Syria, Saddam's Iraq and Iran -- precludes any relations. As for their neighbor to the north, many Iraqi Kurds blame the development of Israel's relationship with Turkey for preventing real progress in Israeli-Kurdish relations. While Turkey is no friend of Saddam and cooperated in the establishment of the autonomous zone, the Kurdish national issue remains a highly sensitive one within Turkey, largely because of the campaign of terror waged inside that country by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) .

Iraqi Kurds do retain some connection with Israel via the airwaves and cyberspace. Iraqis generally distrust state television. There's a joke about a man who complains that the black-and-white TV he bought in a Baghdad market doesn't work. The merchant pastes a photo of Saddam Hussein on the screen, and exclaims, "See, it works fine. And now it's in color."

But north of the Kurds' line of control, the media situation isn't nearly as dire. Over 50 newspapers are available in Sulaymaniyah, ranging from the Baghdad official press to Kurdish and Assyrian local publications. In Iraq proper, only Baath Party papers are allowed. Those who can afford the $400 satellite receiver can access the BBC and CNN. Still, many Iraqis rely on the Voice of Israel in Arabic for their news.

A personal experience makes the point. Last spring, I sat in a shared taxi near the dividing line of territory controlled by the PUK and KDP, as a PUK peshmurga (militia man) rummaged through the trunk in search of weapons. Another soldier gazed upward at the clouds rolling over the drought-stricken region. "Do you think it's going to rain?" he asked his comrade. "Yes," was the response, "Israel Radio said it would rain, so it will rain." An hour later I was caught in a downpour.

The Kurds also get Israeli TV via satellite. Hotels in the north program guest TVs to receive Israel's Channel 2, and some students in Sulaymaniyah tune in for the American films.

While the Internet is available only to Baath Party elite in the rest of Iraq, the north is fully connected. Sulaymaniyah and other cities boast numerous Internet cafes and home connections. In ministries, universities and cafes, agronomists surf the website of Ben-Gurion University for hints on desert agriculture, while newspaper columnists and policy-makers check Tel Aviv University's Dayan Center site for the latest developments in Middle East policy.

The personal Kurdish-Jewish/Israeli connection, however, is clearly fading. The older generation of Iraqi Kurds fondly remember Jewish neighbors and friends, most of whom left in the late 1940s and 50s, but younger people don't have the same recollections. Residents of Halabja, Sulaymaniyah, Irbil, Akre and Zakho can still point out what used to be the Jewish quarters, but finding old synagogues and graveyards proves much more difficult. In Amadya, residents recently argued over where the Jewish graveyard had been -- even though a centuries-old Jewish community had departed just decades earlier.

And as Jews themselves become less familiar, the positive image of both Israel and Jews is, inevitably, on increasingly shaky grounds. The militant Saudi-financed Islamic Unity Movement of Kurdistan, which has grown up along the Iranian border, and its off-shoots tap into dissatisfaction with the arrogance and petty corruption of local administrations in both the PUK- and KDP-administered regions. The Islamists have tens of thousands of adherents today and won over 70 percent of the vote in Halabja in the last elections.

Saudi-funded mosques and schools preach virulently anti-Israel and anti-Semitic lessons. A popular myth circulated by Islamists in the Gulf and Egypt last year, that Pepsi is a secret Jewish acronym for "Purchase Every Pepsi and Support Israel," is making the rounds in Halabja. A university student from Tawella insisted that the Crusades had been fought between the Jews and the Muslims, as he had been taught by a teacher from the Wahabbi sect that holds sway in Saudi Arabia. There are university students who genuinely believe that Jews control the United Nations, and that Jews dominate the U.S. government.

But there are also residents of the safe haven who envision a region where Jews, Arabs, Kurds, Persians, and Turks can live in relative peace, and not only accept Israel, but also uphold the Jewish state's success as a model to be implemented in their own troubled corner of the Middle East. As one university professor commented, "What we want is to get rid of Saddam so that we can do what the Jews did in Israel. We have a diaspora. People will work furiously hard. All we need is security."

And while Kurds may have a special affinity for Israel, the Iraqis' wider disgust with Saddam may make the feeling even more general. A Kurdish pharmacist from Baghdad, visiting friends in the safe haven, told how a mullah who had come to fill a prescription had commented that he would "welcome an Israeli flag over Baghdad so long as they threw out Saddam and then left us to our business. We couldn't care less about Arab nationalism," the mullah told the pharmacist. "We're not crazy like Syria. We just want to rebuild our country."

Michael Rubin is an adjunct scholar at The Washington

Institute for Near East Policy, and a visiting fellow at Hebrew University's

Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations. He spent the 2000-2001

academic year teaching in Northern Iraq as a Carnegie Council fellow.

![]()

4. - Iraq Press - "Baghdad Renews Contacts With

Pro-Kurdish Tribes":

The Iraqi government is trying to rally Kurdish tribes within areas

under its control through largesse and other benefits.

The move comes amid heightened tension as the government builds up troops in areas close to the semi-independent Kurdish enclave outside its jurisdiction.

The authorities hope to use the tribesmen as foot soldiers to destablise the Kurdish- ruled areas following reports that leaders of the main Kurdish parties have spurned recent calls by President Saddam Hussein for a dialogue.

It is not clear how far the government will succeed in mobilizing Kurds living in areas under its control particularly in the northern city of Mosul and the oil-rich center of Kirkuk.

About one million Kurds live outside the Kurdish-controlled enclave many of them with relatives and families in Kurdish-held areas.

Iraqi government's move also comes at a critical juncture. Many observers believe the United States is intent to use the Kurdish region as a launch pad for attacking Saddam's regime.

The measure also follows a crucial visit by a U.S. Department delegation to the region, which the observers interpret as a gesture of continued U.S. commitment to the protection of Kurds.

The delegation, led by senior State Department official Ryanb Crocker, met leaders of the two main parties in the region. The leaders, Massoud Barzani of the Kurdistan Democratic Party and Jalal Talabani of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, have both expressed satisfaction with the visit.

It is not the first time the authorities try to use Kurds against Kurds. Pro-government Kurds in Mosul formed the bulk of the so-called ''national battalions'', which the authorities deployed to quell rebellion in northern Iraq.

Kurdish sources, speaking on condition of anonymity, say the authorities were reviving the battalions in the hope of using them in any operations against the rebels.

The pro-government Kurds have recently lost prestige and credibility in the eyes of their countrymen. The government hopes to resurrect their influence once again.

Apart from cash, weapons and other benefits the government is said to be giving each of the Kurdish tribal chiefs in its areas huge amounts of diesel fuel almost free of charge to sell on the open market.

One source told Iraq Press that each chief is given on average 6,000 liters of diesel per day. The amount at current prices is worth up to 700,000 dinars (about 450 dollars) - a huge sum in Iraq.

The source said certain tribal chiefs were getting up

to 20,000 liters a day. The government apparently hopes the chiefs will

make enough money to recruit their men for yet another fight with their

ethnic brethren in the north. ![]()

5. - AFP - "Turkish FM pledges support for new Afghan administration":

KABUL

Turkish Foreign Minister Ismail Cem pledged his country's support

for Afghanistan's interim administration Monday, committing Ankara to

a key role in rebuilding a country ravaged by two decades of war. Cem,

who formally reopened Turkey's diplomatic mission in Kabul during his

one-day visit to the Afghan capital, met representatives of the interim

cabinet due to formally assume power on December 22.

He held talks with president Burhanuddin Rabbani, who is aligned with the Northern Alliance, as well as Mohammad Qasim Fahim and Yunus Qanooni, who hold the defence and interior portfolios respectively in Afghanistan's interim administration. "We are ready to help the Afghan people and the new Afghan government on every issue in every field," Cem said. "We are offering Turkey's expertise and experience in restructuring of civilian and military institutions."

Cem also flagged Ankara's willingness to provide "legal, medical, military and educational experts" should that be requested by the new administration, which will be headed by interim leader Hamid Karzai. Karzai left for Rome Monday for talks with former Afghan monarch Mohammed Zahir Shah. The Turkish foreign minister, flanked by special forces commandos from his homeland, also travelled to the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif for talks in the stronghold of Northern Alliance commander Abdul Rashid Dostam. The ethnic Uzbek commander, who lived in exile in Turkey before returning to Afghanistan last April, has criticised the accord struck in Bonn earlier this month, arguing the dominant Tajik factions of the alliance had monopolised key ministerial portfolios.

"The meetings gave me hope that the new Afghanistan will be strong, conscious of its strategic importance and will contribute to peace and stability in this turbulent region," Cem said. "They have all decided to give up war and to take up peace and they referred to a new Afghanistan and to a new ideal which consists of national unity, democracy and human rights." A diplomat accompanying the foreign minister said that Dostam had been told "that the Bonn agreement is rare chance for peace that should not be wasted". He added that Dostam had indicated he was "fed up" with the fighting that has plagued Afghanistan ever since the 1979 Soviet invasion. Turkey, the only Muslim nation that is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), lent its support to the US-led campaign against the Taliban theocracy and Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda network in Afghanistan. Turkey has also indicated its willingness to join any multinational peacekeeping force deployed in Afghanistan under the nominal leadership of Britain.

However, Ankara agreed "with the Afghans that any

armed force should be present in Afghanistan only in measure with the

need and the demand of the Afghan people -- we reject any foreign intervention",

Cem said. Cem's flight to Kabul also ferried in several tonnes of humanitarian

aid, including medical supplies slated for the Turkish-funded Ataturk

children's hospital in Kabul. Cem was scheduled to return to the Pakistani

capital of Islamabad later Monday for discussions with his Pakistani

counterpart Abdul Sattar. Turkey closed its diplomatic mission here

after the Taliban seized Kabul from Rabbani in 1996. ![]()

6. - Middle East Newsline - "U.S. miffed by Turkey`s cooperation with Iraq":

WASHINGTON

The United States is expressing unease with Turkey's continued economic

cooperation with Iraq.

U.S. officials said the Bush administration has urged Ankara to reduce new forms of cooperation with the regime of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. The officials said Turkey must join a U.S.-led front that opposes Saddam and his efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction.

So far, the officials said, Turkey's response has been mixed. Ankara seeks to cooperate with Washington on military issues concerning Iraq. But the government of Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit said Iraq remains a key trading partner for Turkey.

On Wednesday, the State Department expressed opposition

to a second border crossing between Iraq and Turkey. The border gate

was meant to facilitate Iraqi oil exports -- most of them not under

United Nations supervision - to Turkey. ![]()